Building computers from discrete components is a fairly common hobby project, but it used to be the only way to build a computer until integrated circuits came on the scene. If you’re living in the modern times, however, you can get a computer like this running easily enough, but if you want to dive deep into high performance you’ll need to understand how those components work on a fundamental level.

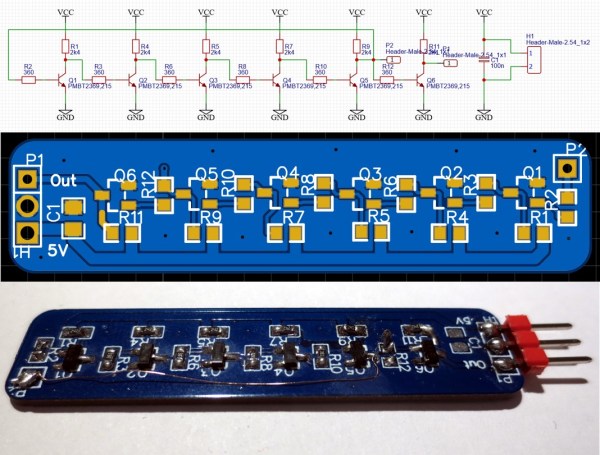

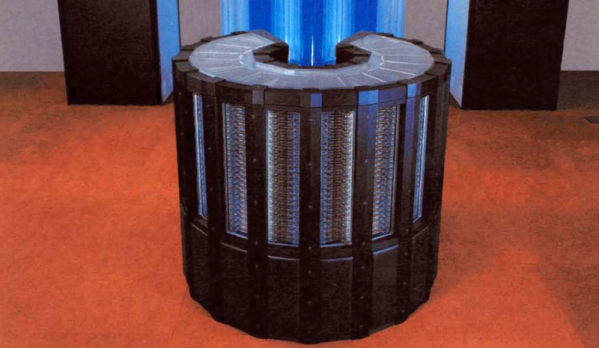

[Tim] and [Yann] have been working on replicating circuitry found in the CDC6600, the first Cray supercomputer built in the 1960s. Part of what made this computer remarkable was its insane (for the time) clock speed of 10 MHz. This was achieved by using bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) that were capable of switching much more quickly than typical transistors, and by making sure that the support circuitry of resistors and capacitors were tuned to get everything working as efficiently as possible.

The duo found that not only are the BJTs used in the original Cray supercomputer long out of production, but the successors to those transistors are also out of production. Luckily they were able to find one that meets their needs, but it doesn’t seem like there is much demand for a BJT with these characteristics anymore.

[Tim] also posted an interesting discussion about some other methods of speeding up circuitry like this, namely by using reach-through capacitors and Baker clamps. It’s worth a read in its own right, but if you want to see some highlights be sure to check out this 16-bit computer built from individual transistors.