Most 3D printer filament soaks up water from the air, and when it does, the water passing through the extruder nozzle can expand, bubble, and pop, causing all kinds of mayhem and unwanted effects in the print. This is why reels come vacuum sealed. Some people 3D print so much that they consume a full roll before it can soak up water and start to display these effects. Others live in dry climates and don’t have to worry about humidity. But the rest of us require a solution. To date, that solution has been filament dryers, which are heated elements in a small reel-sized box, or for the adventurous an oven put at a very specific temperature until the reel melts and coats the inside of the oven. The downside to this method is that it’s a broad stroke that takes many hours to accomplish, and it’s inefficient because one may not use the whole roll before it gets soaked again.

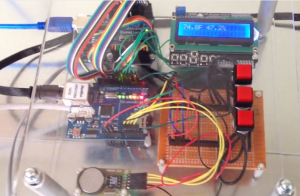

In much the same way that instant water heaters exist to eliminate the need for a water heater, [3DPI67] has a solution to this problem, and it involves passing the filament through a small chamber with a heating element and fan circulating air. The length of the chamber is important, as is the printing speed, since the filament needs to have enough time in the improvised sauna to sweat out all its water weight. The temperature of the chamber can’t get above the glass transition temperature of the filament, either, which is another limiting factor for the dryer. [3DPI67] wrote up a small article on his improvised instant filament heater in addition to the video.

So far, only TPU has been tested with this method, but it looks promising. Some have suggested a larger chamber with loops of filament so that more can be exposed for longer. There’s lots of room for innovation, and it seems some math might be in order to determine the limits and optimizations of this method, but we’re excited to see the results.

The kiln is built from slightly blemished pallet rack shelving that [Tim] cut to suit his needs. He skinned it with 1/2″ insulation boards sealed with aluminium tape and plans to add sheet metal to protect the insulation.

The kiln is built from slightly blemished pallet rack shelving that [Tim] cut to suit his needs. He skinned it with 1/2″ insulation boards sealed with aluminium tape and plans to add sheet metal to protect the insulation. This project is

This project is