In this tremendously educational video, [Linus Åkesson] takes us through how he develops a synthesizer and a sequencer and editor for it on the Commodore 64, all in BASIC. While this sounds easy, [Linus] is doing this in hard mode: all of the audio is generated by POKE, and it gets crazier from there. If you’re one of those people out there who think that BASIC is a limited language, you need to watch this video.

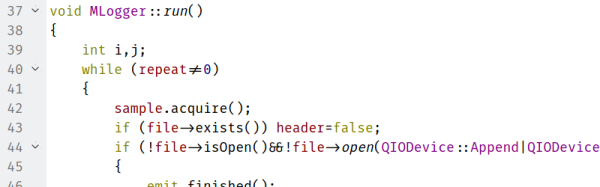

[Linus] can do anything with POKE. On a simple computer like the C64, the sound chip, the screen chips, and even the interrupts that control program flow are all accessible simply by writing to the right part of memory. So the main loop here simply runs through a lot of data, POKEing it into memory and turning the sound chip on and off. There’s also a counter running inside the C64 that he uses to point into a pitch lookup table in the code.

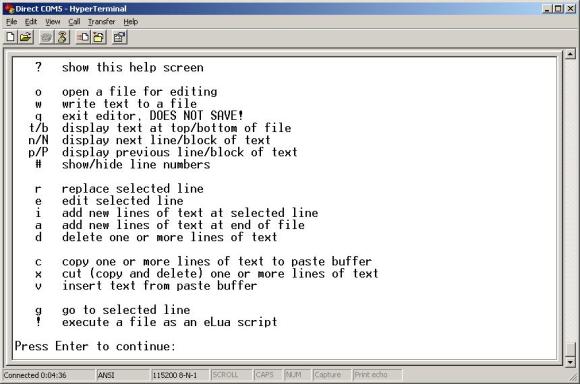

But the inception part comes when he designs the sequencer and editor. Because C64 BASIC already has an interactive code editor, he hijacks this for his music editor. The final sequencer interface exists inside the program itself, and he writes music in the code, in real time, using things like LIST and editing. (Code is data, and data is code.) Add in a noise drum hack, and you’ve got some classic chiptuney sounds by the end.

We love [Linus]’s minimal C64 exercises, and this one gets maximal effect out of a running C64 BASIC environment. But that’s so much code in comparison to his 256-byte “A Mind is Born” demo. But to get that done, he had to use assembly.

Thanks [zogzog] for the great tip!

Continue reading “Linus Live-Codes Music On The Commodore 64”