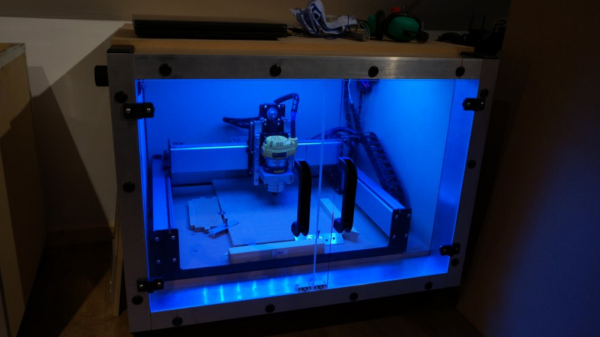

Setting up a desktop CNC brings along two additional problems that need to be resolved – noise and dust. [Nick] upgraded from a Shapeoko2 to the Shapeoko3 and decided to build a fresh dust and noise proof enclosure for his CNC , and it turned out way better than he had anticipated.

When trying to build something like this, aluminium extrusions seem like the obvious choice for the structure. Instead, he opted for low-cost steel frame shelving units. The 3mm thick steel frame results in a nice rigid structure. The top and bottom were lined with 18mm thick MDF panels. For the two sides and back, he choose 60mm noise dampening polyurethane foam lined with 6mm MDF on both sides, and held together with spray adhesive and tight friction fit in the frame.

The frame was a tad shallower and caused the spindle of the Shapeoko3 to stick out the front. To take care of this, he installed an additional aluminium frame to increase the depth of the enclosure. This also gave him a nice front surface on which to mount the 10mm thick polycarbonate doors. The doors have magnetic latches to hold them close, and an intentional gap at the top allows air to enter inside the enclosure. A 3D printed outlet port was fixed to the side wall, where he can attach the vacuum hose for dust collection. The final step was to add a pair of industrial door handles and a bank of blue LED strip lights inside the enclosure for illumination.

It’s a simple build, but well executed and something that is essential to keep the shop clean and dampen noise.