Typically, if you’re shooting 35 mm film, you’re using it in an old point-and-shoot or maybe a nice SLR. You might even make some sizeable prints if you take a particularly good shot. But you can get altogether weirder with 35 mm if you like, as [Socialmocracy] demonstrates with his “extreme sprocket hole photography” project (via Petapixel).

The concept is simple enough. [Socialmocracy] wanted to expose four entire rolls of 35 mm film all at the same time in one single shot. To be absolutely clear, we’re not talking about exposing a frame on each of four rolls at once. We’re talking about a single exposure covering the entire length of all four films, stacked one on top of the other.

To achieve this, an old-school Cirkut No.6 Outfit camera was pressed into service. It’s a large format camera, originally intended for shooting panoramas. As the camera rotated around under the drive of a clockwork motor, it would spool out more film to capture an image.

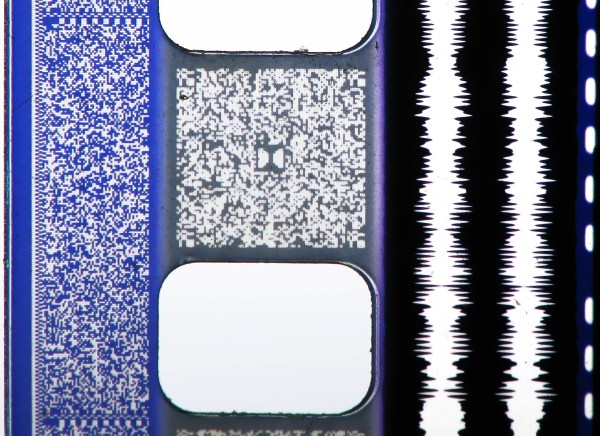

[Socialmocracy] outfitted the 100-year-old camera with a custom 3D-printed spool that could handle four rolls of film at once, rather than its usual wide single sheet of large format film. This let the camera shoot its characteristic panoramas, albeit spread out over multiple rolls of film, covering the sprocket holes and all. Hence the name—”extreme sprocket hole photography.”

It’s a neat build, and one that lets [Socialmocracy] use more readily available film to shoot fun panoramas with this old rig. We’ve featured some other great film camera hacks over the years, too, like this self-pack Polaroid-style film. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Using Four Rolls Of Film To Make One Big Photo” →