When Pano Logic went out of business in 2012, their line of unique FPGA-based thin clients suddenly became a burden that IT departments didn’t want anything to do with. New and used units flooded the second-hand market, and for a while you could pick these interesting gadgets up for not much more than the cost of shipping. Thanks to considerable interest from the hacking community the prices for these boxes have climbed a bit on eBay, but they’re still a great way to get your feet wet with FPGA hacking.

Especially now, as Pano Logic fanatic [Skip Hansen] has figured out how to flash a new firmware on them without having to crack open the case and break out the JTAG or SPI programmer. For the seasoned hardware hacker that might not seem like a big deal, but if you’re new to the game or just more interested in the software side of the equation, this trick makes things considerably more accessible. Having an external programmer is still a good idea if things go south, but if you’re just looking to flash some demos and see what the hardware is capable of this is a huge quality of life improvement.

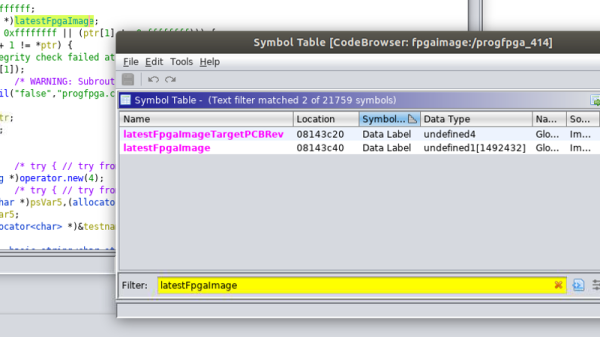

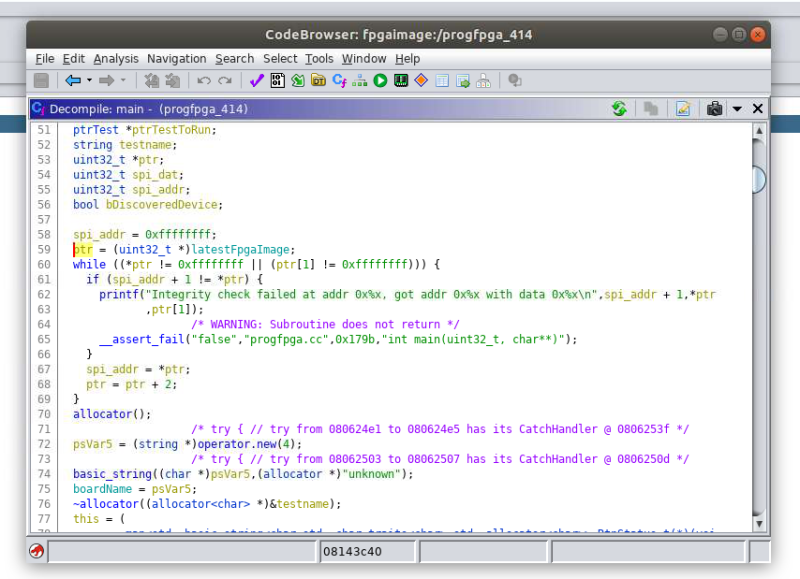

Even if you aren’t interested in fiddling with the orphaned products of a defunct Bay Area startup, the write-up is a fascinating look at practical software reverse engineering. As it turns out, [Skip] didn’t create this new firmware update tool from scratch. He actually opened up the official Linux update utility from Pano Logic in Ghidra and was able to figure out where the firmware image actually lived inside the program. He then wrote his own tool in C which will patch the update tool with a user-supplied firmware image.

Even if you aren’t interested in fiddling with the orphaned products of a defunct Bay Area startup, the write-up is a fascinating look at practical software reverse engineering. As it turns out, [Skip] didn’t create this new firmware update tool from scratch. He actually opened up the official Linux update utility from Pano Logic in Ghidra and was able to figure out where the firmware image actually lived inside the program. He then wrote his own tool in C which will patch the update tool with a user-supplied firmware image.

After patching, all you need to do is follow the official update procedure, which Pano Logic helpfully documented in the YouTube video after the break. [Skip] mentions he didn’t find any clear license information in the official software he was fiddling with, and of course with the company out of business it’s not too likely anyone is going to come knocking down his door anyway. Still, he says the downloads for the Pano Logic updater are still floating around on the tubes out there for you to find, so he’s not distributing anyone’s code but his own in this project.

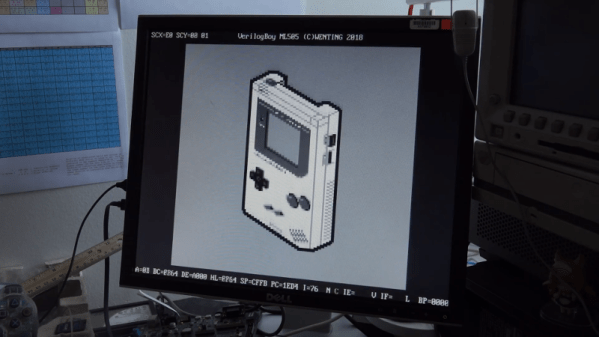

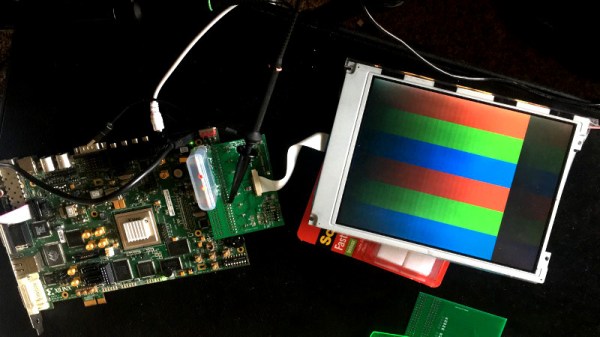

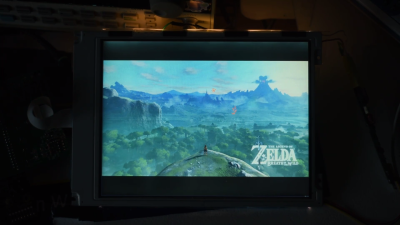

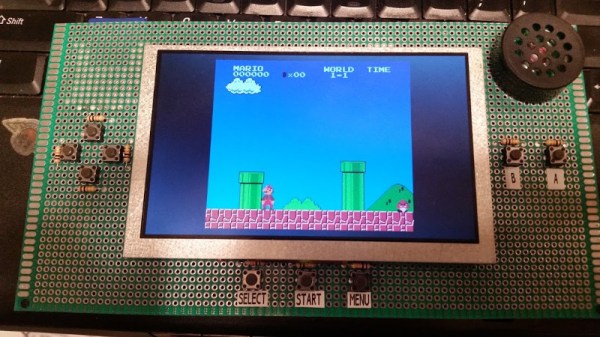

There are a number of hackers out there working to turn the Pano Logic thin clients into useful general purpose FPGA platforms, such as [Tom Verbeure], who’s incredible graphics demos got [Skip] inspired to grab his own unit off eBay. With support for USB and SDRAM added by [Wenting Zhang] while getting his FPGA GBA emulator running on the hardware, it seems there’s never been a better time to get on the Pano Logic train.