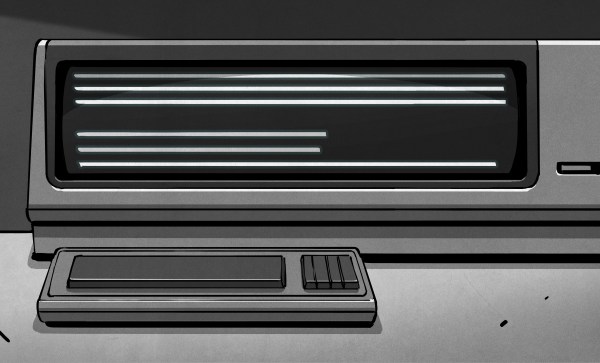

We know that the Hackaday family includes many enthusiasts for quality keyboards, and thus mention of the fabled ‘boards of yore such as the IBM Model F is sure to set a few pulses racing. Few of us are as lucky as [Brennon], who received the familial IBM PC-XT complete with its sought-after keyboard.

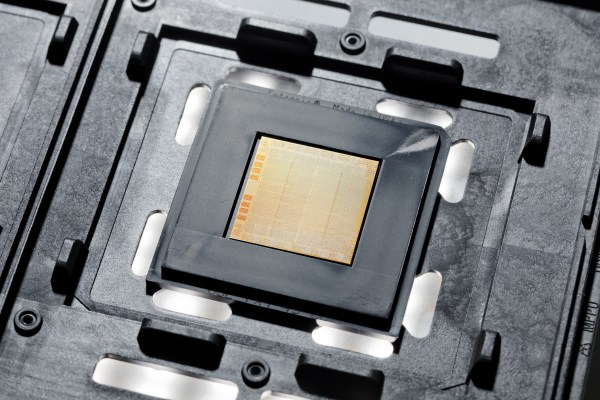

This Model F has a manufacture date in March 1983, and as a testament to its sturdy design was still in one piece with working electronics. It was however in an extremely grimy condition that necessitated a teardown and deep clean. Thus we are lucky enough to get a peek inside, and see just how much heavy engineering went into the construction of an IBM keyboard before the days of the feather-light membrane devices that so many of us use today. There follows a tale of deep cleaning, with a Dremel and brush, and then a liberal application of Goo Gone. The keycaps had a long bath in soapy water to remove the grime, and we’re advised to more thoroughly dry them should we ever try this as some remaining water deep inside them caused corrosion on some of the springs.

The PC-XT interface is now so ancient as to have very little readily available in the way of adapters, so at first a PS/2 adapter was used along with a USB to PS/2 converter. Finally though a dedicated PC-XT to USB converter was procured, allowing easy typing on a modern computer.

This isn’t our first look at the Model F, but if you can’t afford a mechanical keyboard don’t worry. Simply download a piece of software that emulates the sound of one.