Given that we live in the proverbial glass house, we can’t throw stones at [ellis.codes] for modifying a perfectly fine Vornado fan. He’d picked that fan in the first place because, unlike most fans, it had a DC motor. Of course, DC motors are easier to control with a microcontroller, and next thing you know, it was sporting an ESP32 and a WiFi interface.

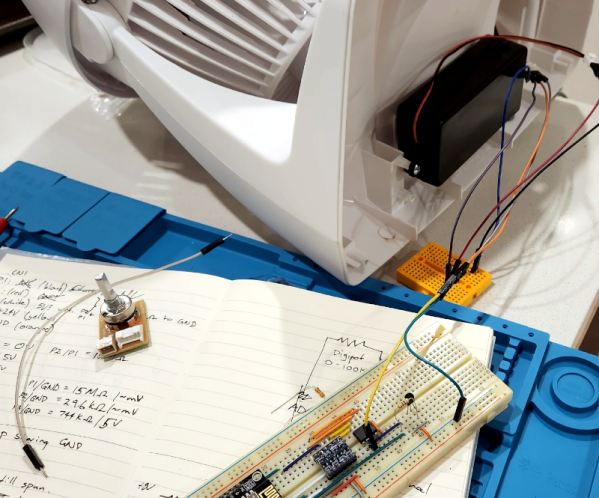

The original fan was surprisingly sparse inside. A power supply, of course, and just a tiny PCB for a speed control. Oddly, it looks like the speed control was just a potentiometer and a 24 V supply. It wasn’t clear if the “motor” had some circuitry in it to do PWM control or not. That seems likely, though.

Regardless, the project opted for a digital pot IC to maintain compatibility. One nice thing about the modification is that it replaces the existing board with the same connectors. So if you wanted to revert the fan to normal, you simply have to swap the boards back.

Now the fan talks to home automation software. Luckily, there’s still nothing wrong with it. We love seeing bespoke ESPHome projects. Even if your fan has WiFi, you might not like it communicating with Big Brother.