If there’s one lesson to be learned from [Aled Cuda]’s pulsed laser driver, it’s that you can treat the current limits on electronic components as a suggestion if the current duration is measured in nanoseconds.

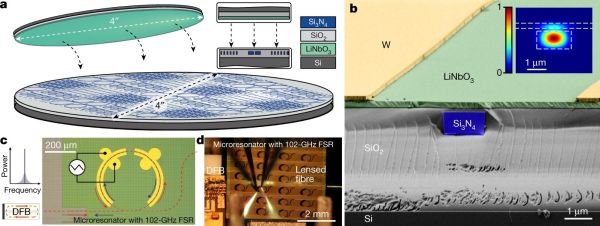

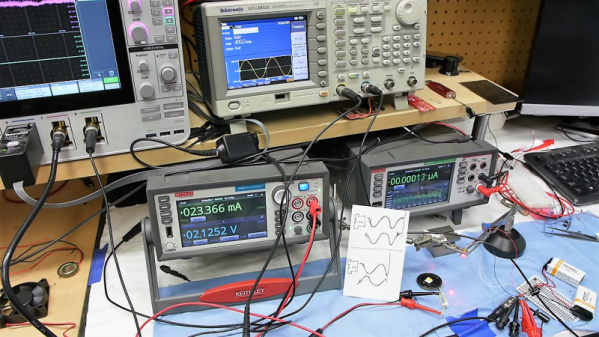

The components in question are a laser diode and an NPN transistor, the latter of which operates in avalanche mode to drive nanosecond-range pulses of high current through the former. A buck-boost converter brings a 12 volt power supply up to 200 volts, which then passes through a diode and into the avalanche transistor, which is triggered by an external pulse generator. On the other side of the transistor is a pulse-shaping network of resistors and capacitors, the laser diode, and a parallel array of low-value resistors, which provide a current monitor by measuring the voltage across them. There is an optoisolator to protect the pulse generator from the 200 volt lines on the circuit board, but for simplicity’s sake it was omitted from this iteration; there is some slight irony in designing your own laser driver for the sake of the budget, then controlling it with “a pulse generator we don’t mind blowing up.” We can only assume that [Aled] was confident in his work.

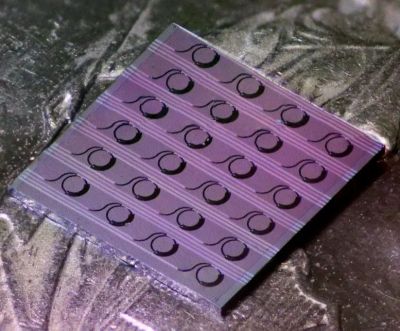

The video below details the assembly of the circuit board, which features some interesting details, such as the use of a transparent solder mask which makes the circuit layout clear while still helping to align components during reflow. The circuit did eventually drive the diode without destroying anything, even though the pulses were probably 30 to 40 watts. A pulse frequency of 360 hertz gave a nice visual beating effect due to small mismatches between the pulse frequency of the driver and the frame rate of the camera.

This isn’t the first laser driver to use avalanche breakdown for short, high-power pulses, but it’s always good to see new implementations. If you’re interested in further high-speed electronics, we’ve covered them in more detail before.

Continue reading “Driving A Laser At 200 Volts For Nanoseconds”