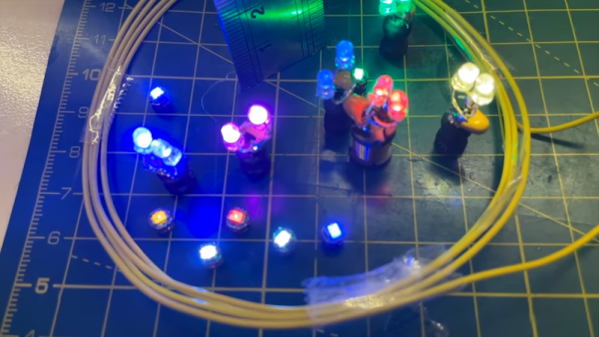

Multiplexing is a very old technology in which control signals are intermixed for the sake of being able to control more devices than there are control signals. For [mihai.cuciuc], the problems started when he multiplexed some very efficient LEDs.

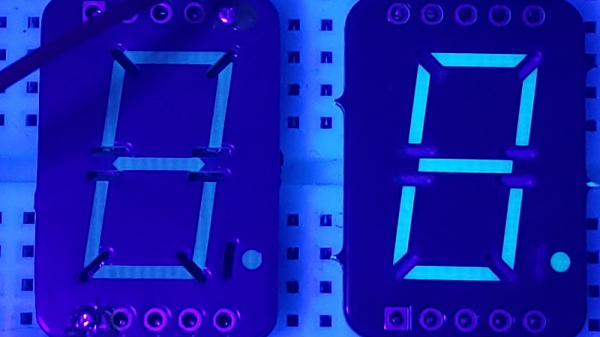

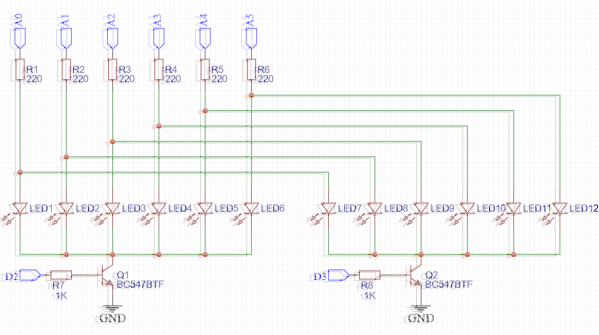

The problem? In two banks of six LEDs each, both LEDs connected to a single Arduino pin would light, even when only one bank was turned on at the ground side. The LED In the bank that was switched on lit brightly, and its corresponding LED in the bank that was off would also be very dimly lit. [mihai] was able to determine that the problem was not due to a leaky transistor, but rather due to a quality of the LEDs themselves.

What is an LED but a diode, and it’s well known that diodes also have capacitance. In fact, this quality is exploited in varactor diodes, a specialty diode whose capacitance can be changed by varying the voltage on the cathode. [mihai] deduced that this capacitance was causing current to flow in the bank that was off. Where was the current going? From the Arduino pin that was on, through its attached LED, and then into the rest of the bank of LEDs, charging them like capacitors. [mihai] hasn’t seen this before, but theorizes that for the latest batch of high efficiency LEDs, this minute current is enough to light the LED through which the current is flowing.

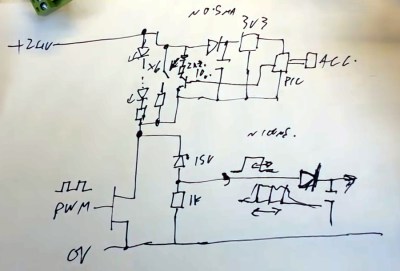

[mihai]’s solution is an elegant hack which he’s made available for your perusal. You might also enjoy this introduction to diode basics by W2AEW. If you have any great diode or LED hacks of your own, be sure to drop us a line!

Here at Hackaday, we pride ourselves on bringing you the very freshest of hacks. But that doesn’t mean we catch all the good stuff the first time around, and occasionally we get a tip on an older project that really should have been covered the first time around.

Here at Hackaday, we pride ourselves on bringing you the very freshest of hacks. But that doesn’t mean we catch all the good stuff the first time around, and occasionally we get a tip on an older project that really should have been covered the first time around.