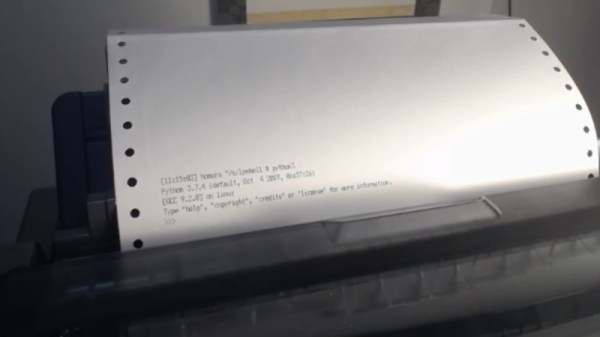

Back in the early days of computing, user terminals utilized line printers for output. Naturally this took an incredible amount of paper, but it came with the advantage of creating a hard copy of everything you did. Plus it was easy to annotate the terminal output with nothing more exotic than a ballpoint pen. But once CRT displays became more common, these paper terminals (also known as teleprinters, or teletypes) quickly fell out of style.

A fan of nostalgic hacks, [Drew DeVault] recently tried to recreate the old-school teletype experience with (somewhat) more modern hardware. He picked up an Epson LX-350 line printer, and with a relatively small amount of custom code, he was able to create a fairly close approximation of what it would have been like to use one of these terminals. He’s published all the source code, so if you’ve got an old line printer and a Linux box, you too can learn what it was like to measure your work day in reams of paper.

This is made possible by the fact that the modern Linux virtual terminal is simply a userspace emulation of those physical terminals of yore. [Drew] just need to write some code that would essentially spawn a shell on the Linux USB line printer device, plus sprinkle in some quality of life improvements such as using Epson’s proprietary ANSI escape sequences to feed the paper out far enough so the user can see what it says before pulling it back in to write the next interactive line.

Of course, the experience isn’t perfect as the printer naturally doesn’t have a keyboard attached to it. If you’re looking for something a bit more authentic, you could always convert an old electric typewriter into a modern-ish teletype.

![Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie at a PDP-11. Peter Hamer [CC BY-SA 2.0]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1279px-Ken_Thompson_sitting_and_Dennis_Ritchie_at_PDP-11_2876612463.jpg?w=400)