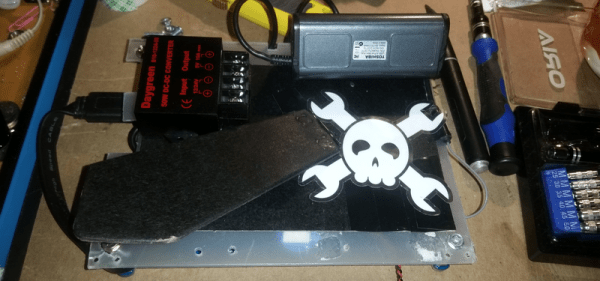

If you’re like us, there’s a creeping feeling that comes over you when you’re placing an order for parts for your latest project: Don’t I already have most of this stuff? With the well-stocked junk bins most of us sport and the stacks of defunct electronics that are almost always within arm’s length, chances are pretty good you do. And yet, we always seem to just click the button and place a new order anyway; it’s just easier.

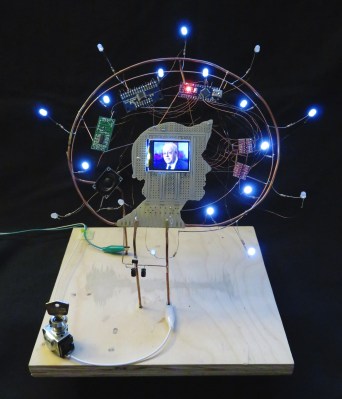

But what if mining the treasure in your junk bin was easier? If you knew right at design time that you had something in your stash you could slot into your build, that would be something, right? That’s the idea behind ecoEDA, a Python-based KiCAD plugin by [Jasmine Lu], [Beza Desta], and [Joyce Passananti]. The tool integrates right into the schematic editor of KiCAD and makes suggestions for substitutions as you work. The substitutions are based on a custom library of components you have on hand, either from salvaged gear or from previous projects. The plug-in can make pin-for-pin substitutions, suggest replacements with similar specs but different pinouts, or even build up the equivalent of an integrated circuit from available discrete components. The video below gives an overview of the tool and how it integrates into the design workflow; there’s also a paper (PDF) with much more detail.

This seems like an absolutely fantastic idea. Granted, developing the library of parts inside all the stuff in a typical junk bin is likely the biggest barrier to entry for something like this, and may be too daunting for some of us. But there’s gold in all that junk, both literally and figuratively, and putting it to use instead of dumping it in a landfill just makes good financial and environmental sense. We’re already awash in e-waste, and anything we can do to make that even just a little bit better is probably worth a little extra effort. Continue reading “EcoEDA Integrates Your Junk Bin Into Your Designs”