Thinkpads are great, especially the old ones. You find a T420, and you can have a battery hanging off the back, a battery in the optical drive bay, and for some old Thinkpads, there’s a gigantic ‘slice’ battery that doubles the thickness of your laptop. Here’s the most batteries in a Thinkpad ever, with the requisite reddit post. It’s 27 cells, with an all-up capacity of 212 Watt-hours. There are two interesting takeaways from the discussion here. First, this may, technically, be allowed on a commercial flight. The FAA limit is 100 Watt-hours per battery, and the Ultrabay is a second battery. You’re allowed two additional, removable batteries on a carry on, and this is removable and reconfigurable into some form that the TSA should allow it on a plane. Of course no TSA agent is going to allow this on a plane so that really doesn’t matter. Secondly, the creator of this Frankenpad had an argument if Hatsune Miku is anime or not. Because, yeah, of course the guy with a Thinkpad covered in Monster energy drink stickers and two dozen batteries glued on is going to have an opinion of Miku being anime or not. That’s just the way the world works.

Prices for vintage computers are now absurd. The best example I can call upon is expansion cards for the Macintosh SE/30, and for this computer you have a few choice cards that have historically commanded a few hundred dollars on eBay. The Micron XCEED Color 30 Video Card, particularly, is a special bit of computer paraphernalia that allows for grayscale on the internal monitor. One of these just sold for two grand. That’s not all, either: a CPU accelerator just sold for $1200. These prices are double what they were just a few years ago. We’re getting to the point where a project to reverse engineer and produce clones of these special cards may make financial sense.

The biggest news in consumer electronics this week is the Playdate. It’s a pocket game console that has a crank. Does the crank do anything? No, except that it has a rotary encoder, so this can nominally be used for games. It will cost $150, and there are zero details on the hardware other than the industrial design was done by Teenage Engineering. There’s WiFi, and games will be delivered wireless on a weekly basis. A hundred thousand people are on the wait list to buy this.

If you want a pick and place in your garage workshop, there aren’t many options. There’s a Neoden for about ten grand, but nothing cheaper or smaller. The Boarditto is a two thousand dollar pick and place machine that fits comfortably on your desk. It has automatic tape feeders, a vision system, and for the most part it looks like what you’d expect a small, desktop pick and place machine to be. That’s all the information for now, with the pre-order units shipping in December 2019.

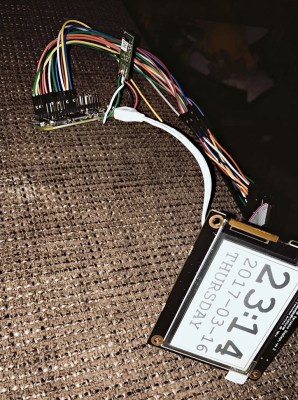

[Jannis Hermanns] couldn’t find a reason to control this outburst of nostalgia for the good old days of small, expensive computers and long hours spent clawing through the LEGO bin to find The Perfect Piece to finish a build. It turns out that the computer part of this replica was the easy part — it’s just an e-paper display driven by a Raspberry Pi Zero. Building the case was another matter, though.

[Jannis Hermanns] couldn’t find a reason to control this outburst of nostalgia for the good old days of small, expensive computers and long hours spent clawing through the LEGO bin to find The Perfect Piece to finish a build. It turns out that the computer part of this replica was the easy part — it’s just an e-paper display driven by a Raspberry Pi Zero. Building the case was another matter, though.

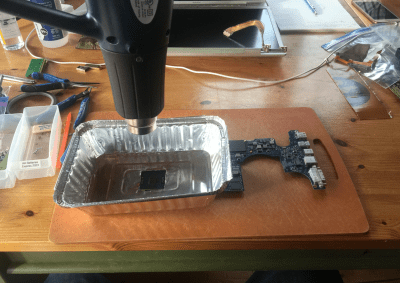

[DocDawning] has a bit of a Mac hoarding problem, and frequently pays $20 for broken laptops of this vintage. Most of the time, the fix is simple: the RAM needs to be reseated, or something like that. Rarely, he comes across a machine that isn’t fixed so easily. The solution, in this case,

[DocDawning] has a bit of a Mac hoarding problem, and frequently pays $20 for broken laptops of this vintage. Most of the time, the fix is simple: the RAM needs to be reseated, or something like that. Rarely, he comes across a machine that isn’t fixed so easily. The solution, in this case,