The best equipment won’t help you if you don’t have it with you in the moment you need it. Knowledge, experience, and a thick skin may help you out there in the mud of the hardware battlegrounds, but they can’t replace a multimeter, an oscilloscope, a logic analyzer, a serial console or a WiFi access point. [Arcadia Labs] has taken on the challenge of combining most of these functions into a single device, developing the Hacker’s equivalent of a Swiss Army Knife: The ESP Swiss Knife.

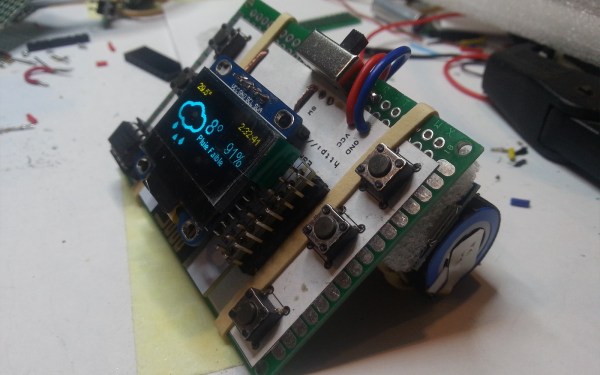

Just like a Swiss Army Knife is first and foremost a knife, the EPS Swiss Knife is first and foremost an ESP8266. That means it is already a great platform for any kind of project, and [Arcadia Labs] supercharged the plain ESP-12E module by adding a couple of useful features commonly used in many projects. There’s an OLED display, four pushbuttons, a temperature sensor, and a Li-Ion cell with a charging module to power the device on the go. A universal “utility socket” breaks out the ESP8266’s leftover GPIOs and the supply voltage for attaching further peripherals.

Just like a Swiss Army Knife is first and foremost a knife, the EPS Swiss Knife is first and foremost an ESP8266. That means it is already a great platform for any kind of project, and [Arcadia Labs] supercharged the plain ESP-12E module by adding a couple of useful features commonly used in many projects. There’s an OLED display, four pushbuttons, a temperature sensor, and a Li-Ion cell with a charging module to power the device on the go. A universal “utility socket” breaks out the ESP8266’s leftover GPIOs and the supply voltage for attaching further peripherals.

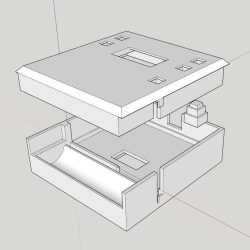

With the hardware up and running, [Arcadia Labs] went on with building a couple of applications to provide the functionality that would make the device earn its name. Among them is a basic oscilloscope, a digital NTP based clock, a thermometer, a WiFi tester, a weather station and a 3D printer status monitor. More applications are planned, such as a chronometer, a timer, a DSLR intervalometer and more. A protective 3D printable enclosure is also in the works. [Arcadia Labs] has been joining the Hackaday Prize 2014 and 2015 before and we’re glad to see another great build coming into existence!

But what, you might ask, makes the 3458A such a significant and desirable instrument? It’s all in the digits. The 3458A is one of the few 8.5 digit multimeters available. It is therefore sensitive to microvolt deflections on 10 volt measurements. It is this ability to distinguished tiny changes on large signals that sets high precision multimeters apart. Imagine weighing an elephant and being able to count the number of flies that land on its back by the change in weight. The 3458A accomplishes a similar feat.

But what, you might ask, makes the 3458A such a significant and desirable instrument? It’s all in the digits. The 3458A is one of the few 8.5 digit multimeters available. It is therefore sensitive to microvolt deflections on 10 volt measurements. It is this ability to distinguished tiny changes on large signals that sets high precision multimeters apart. Imagine weighing an elephant and being able to count the number of flies that land on its back by the change in weight. The 3458A accomplishes a similar feat.