The overall theme of the early part of the Cold War was that of subterfuge — with scientific missions often providing excellent cover for placing missiles right on the USSR’s doorstep. Recently NASA rediscovered Camp Century, while testing a airplane-based synthetic aperture radar instrument (UAVSAR) over Greenland. Although established on the surface in 1959 as a polar research site, and actually producing good science from e.g. ice core samples, beneath this benign surface was the secretive Project Iceworm.

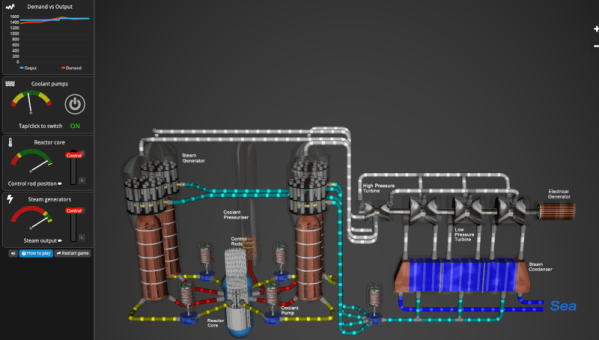

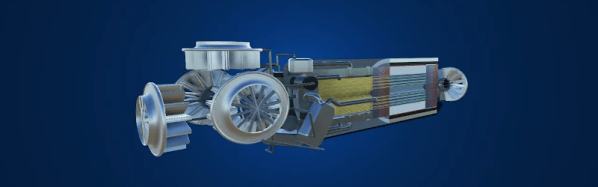

By 1967 the base was forced to be abandoned due to shifting ice caps, which would eventually bury the site under over 30 meters of ice. Before that, the scientists would test out the PM-2A small modular reactor. It not only provided 2 MW of electrical power and heat to the base, but was itself subjected to various experiments. Alongside this public face, Project Iceworm sought to set up a network of mobile nuclear missile launch sites for Minuteman missiles. These would be located below the ice sheet, capable of surviving a first strike scenario by the USSR. A lack of Danish permission, among other complications, led to the project eventually being abandoned.

It was this base that popped up during the NASA scan of the ice bed. Although it was thought that the crushed remains would be safely entombed, it’s estimated that by the year 2100 global warming will have led to the site being exposed again, including the thousands of liters of diesel and tons of hazardous waste that were left behind back in 1967. The positive news here is probably that with this SAR instrument we can keep much better tabs on the condition of the site as the ice cap continues to grind it into a fine paste.

Top image: Camp Century in happier times. (Source: US Army, Wikimedia)