Seeing his wife try to use a cool face mask to get through the pain of a migraine headache, [Sparks and Code] started thinking of ways to improve the situation. The desire to save her from these debilitating bouts of pain drove him to make an actively cooled mask, all the while creating his own headache of an over-engineered mess.

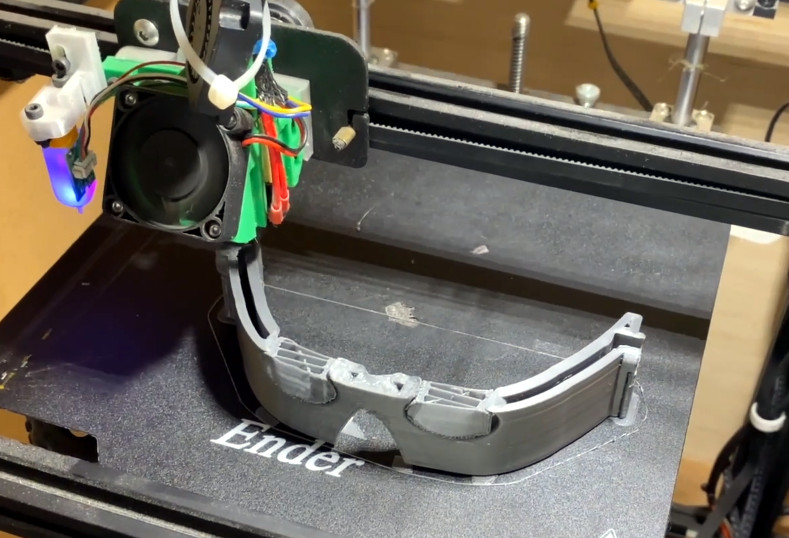

Instead of having to put the face mask into the refrigerator to get it cold, [Sparks and Code] wanted to build a mask that he could circulate chilled water through. With a large enough ice-filled reservoir, he figured the mask should be able to stay at a soothing temperature for hours, reducing the need for trips to the fridge.

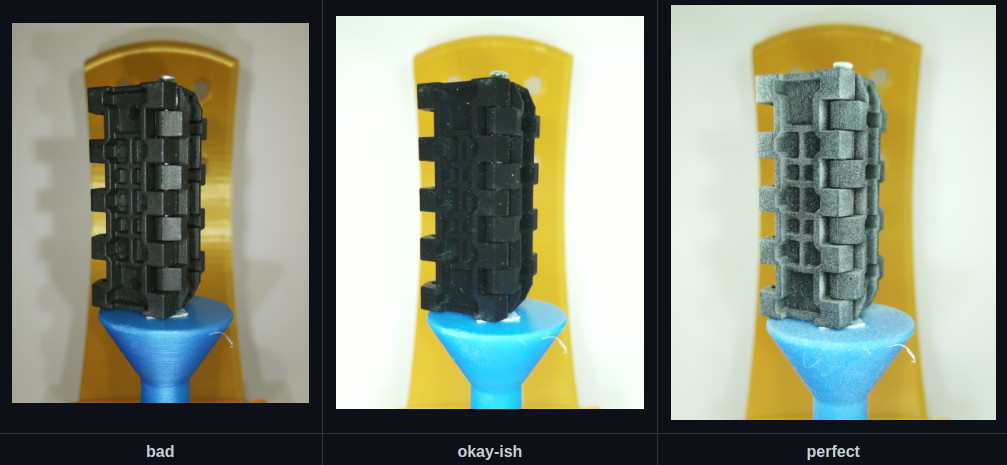

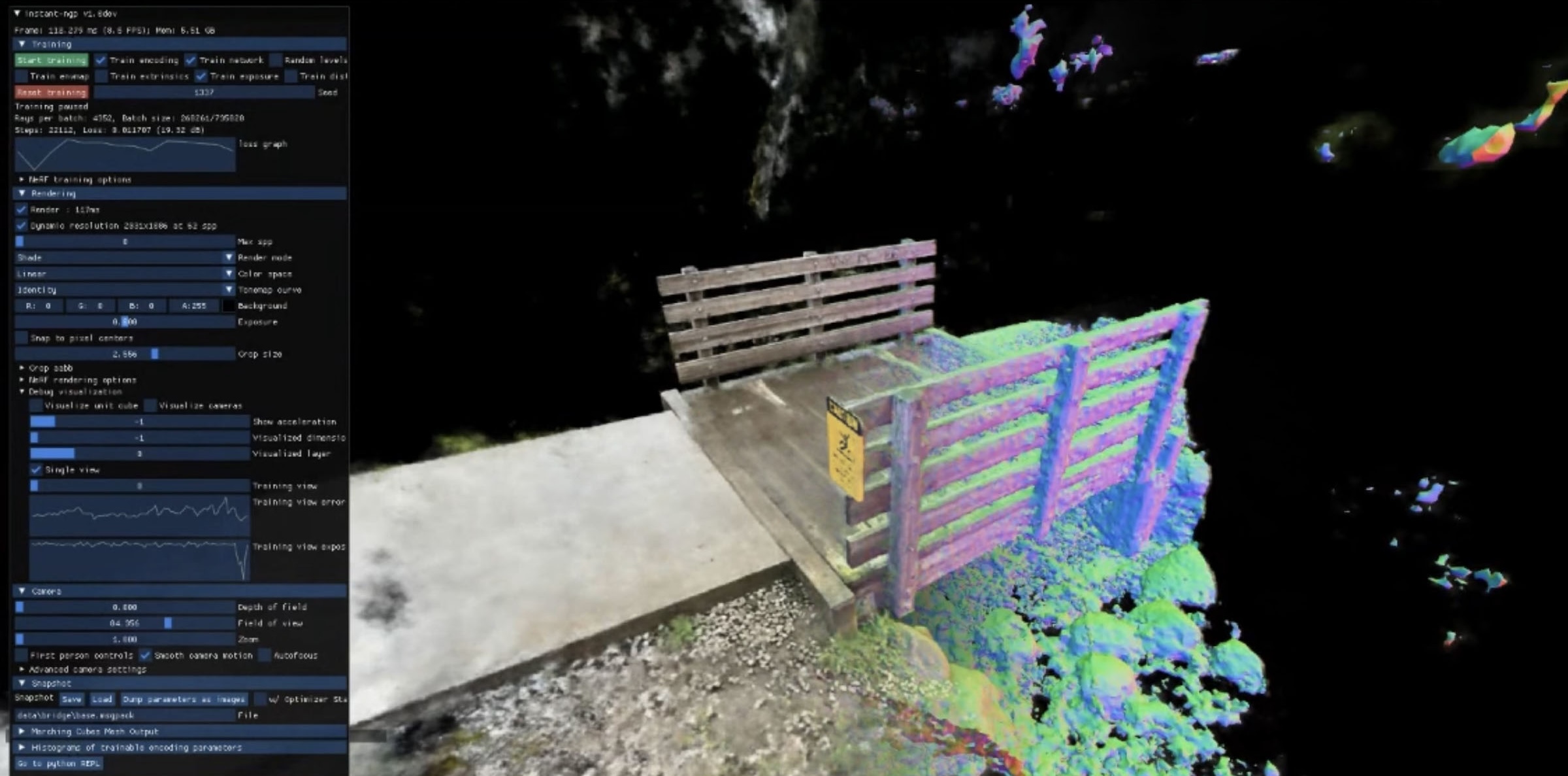

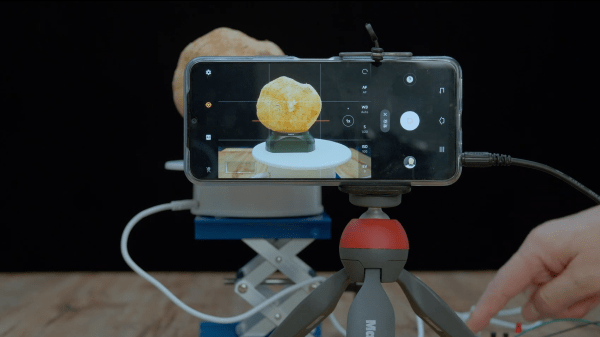

[Sparks and Code] started out by using photogrammetry to get a 3D model of his wife’s face. Lack of a compatible computer and CUDA-enabled GPU meant using Google Cloud to do the heavy lifting. When they started making the face mask, things got complicated. And then came the unnecessary electronics. Then the overly complicated and completely unnecessary instrumentation. The… genetic algorithms? Yes. Those too.

We won’t spoil the ending — but suffice it to say, [Sparks and Code] learned a cold, hard lesson: simpler is better! Then again, sometimes being over-complicated is kind of the point such as in this way-too-complex gumball machine.

Continue reading “Cool Face Mask Turns Into Over-Engineered Headache”