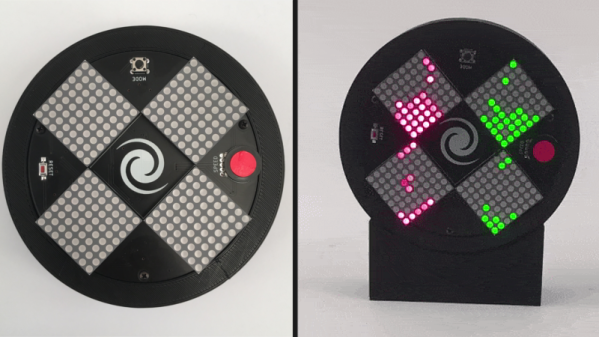

[Fearless Night]’s slick dual hourglass doesn’t just simulate sand with LEDs, it also emulates the effects of gravity on those simulated particles and offers a few different mode options.

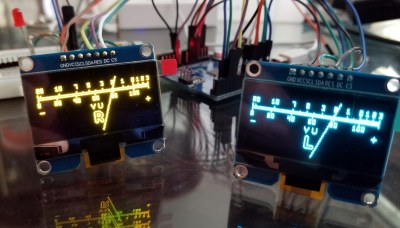

The unit uses an Arduino (with ATMEGA328P) and an MPU-6050 accelerometer breakout board to sense orientation and movement, and the rest is just a matter of software. Both the Arduino and the MPU-6050 board are readily available and not particularly expensive, and the LED matrix displays are just 8×8 arrays of red/green LEDs, each driven by a HT16K33 LED controller IC.

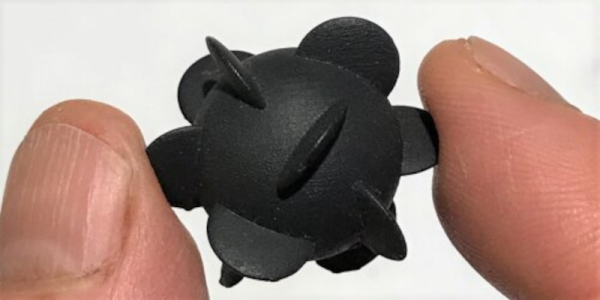

The enclosure and stand are both 3D-printed, and a PCB not only mounts the components but also serves as a top cover, with the silkscreen layer of the PCB making for some handy labels. It’s a clever way to make the PCB pull double-duty, which is a technique [Fearless Night] also used on their earlier optical theremin design.

Those looking to make one of their own will find all the design files and source code handily available from the project page. It might not be able to tell time in the classical sense, but seeing the hourglass displays react to the device’s orientation is a really neat effect.