USB chargers are everywhere and it is the responsibility of every hacker to use this commonly available device to its peak potential. [Septillion] and [Hugatry] have come up with a hack to manipulate a USB charger into becoming a variable voltage source. Their project QC2Control works with chargers that employ Quick Charge 2.0 technology which includes wall warts as well as power banks.

Qualcomm’s Quick Charge is designed to deliver up to 24 watts over a micro USB connector so as to reduce the charging time of compatible devices. It requires both the charger as well as the end device to have compatible power management chips so that they may negotiate voltage limiting cycles.

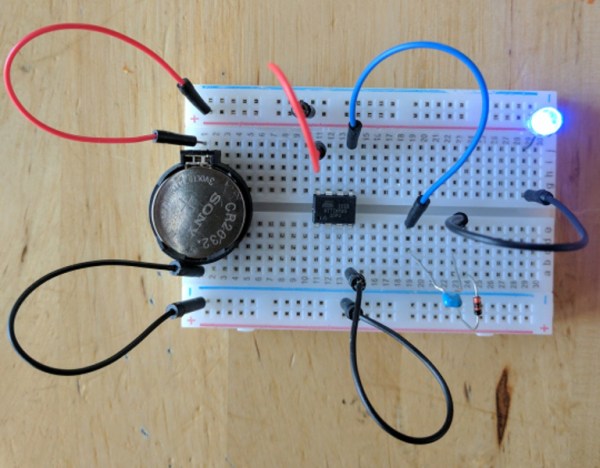

In their project, [Septillion] and [Hugatry] use a 3.3 V Arduino Pro Mini to talk to the charger in question through a small circuit consisting of a few resistors and diodes. The QC2.0 device outputs voltages of 5 V, 9 V and 12 V when it sees predefined voltage levels transmitted over the D+ and D- lines, set by Arduino and voltage dividers. The code provides function calls to simplify the control of the power supply. The video below shows the hack in action.

Quick Charge has been around for a while and you can dig into the details of the inner workings as well as the design of a compatible power supply from reference designs for the TPS61088 (PDF). The patent (PDF) for the Quick Charge technology has a lot more detail for the curious.

Similar techniques have been used in the past and will prove useful for someone looking for a configurable power supply on the move. This is one for the MacGyver fans.

Continue reading “USB Charger Fooled Into Variable Voltage Source”