Nearly three years after the rapid unplanned disassembly of the Arecibo radio telescope, we finally have a culprit in the collapse: bad sockets.

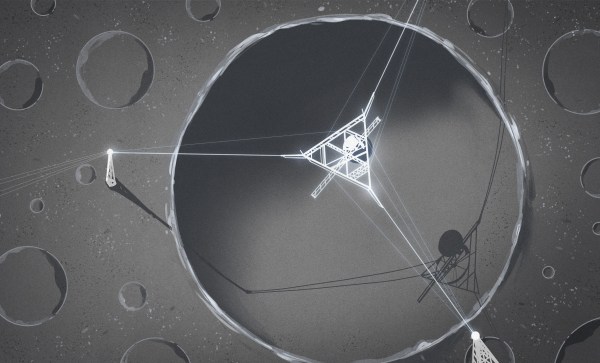

In case you somehow missed it, back in 2020 we started getting ominous reports that the cables supporting the 900-ton instrument platform above the 300-meter primary reflector of what was at the time the world’s largest radio telescope were slowly coming undone. From the first sign of problems in August, when the first broken cable smashed a hole in the reflector, to the failure of a second cable in November, it surely seemed like Arecibo’s days were numbered, and that it would fall victim to all the other bad luck we seemed to be rapidly accruing in that fateful year. The inevitable finally happened on December 1, when over-stressed cables on support tower four finally gave way, sending the platform on a graceful swing into the side of the natural depression that cradled the reflector, damaging the telescope beyond all hope of repair.

The long run-up to the telescope’s final act had a silver lining in that it provided engineers and scientists with a chance to carefully observe the failure in real-time. So there was no real mystery as to what happened, at least from a big-picture perspective. But one always wants to know the fine-scale details of such failures, a task which fell to forensic investigation firm Thornton Tomasetti. They enlisted the help of the Columbia University Strength of Materials lab, which sent pieces of the failed cable to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s High Flux Isotope reactor for neutron imaging, which is like an X-ray study but uses streams of neutrons that interact with the material’s nuclei rather than their electrons.

The full report (PDF) reveals five proximate causes for the collapse, chief of which is “[T]he manual and inconsistent splay of the wires during cable socketing,” which we take to mean that the individual strands of the cables were not spread out correctly before the molten zinc “spelter socket” was molded around them. The resulting shear stress caused the zinc to slowly flow around the cable strands, letting them slip out of the surrounding steel socket and — well, you can watch the rest below for yourself.

As is usually the case with such failures, there are multiple causes, all of which are covered in the 300+ page report. But being able to pin the bulk of the failure on a single, easily understood — and easily addressed — defect is comforting, in a way. It’s cold comfort to astronomers and Arecibo staff, perhaps, but at least it’s a lesson that might prevent future failures of cable-supported structures.

Continue reading “Blame It On The Sockets: Forensic Analysis Of The Arecibo Collapse” →