Hopefully by now most of us know better than to rent a modem from an internet service provider. Buying your own and using it is almost always an easy way to save some money, but even then these pieces of equipment won’t last forever. If you’re sitting on an older cable modem and thinking about tossing it in the garbage, there might be a way to repurpose it before it goes to the great workbench in the sky. [kc9umr] has a way of turning these devices into capable spectrum analyzers.

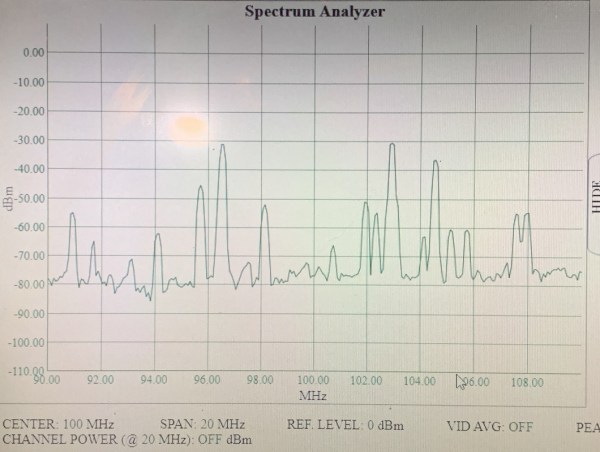

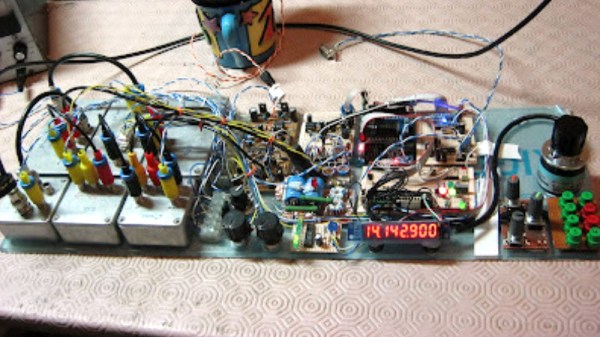

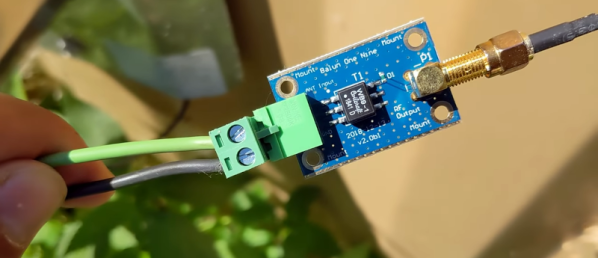

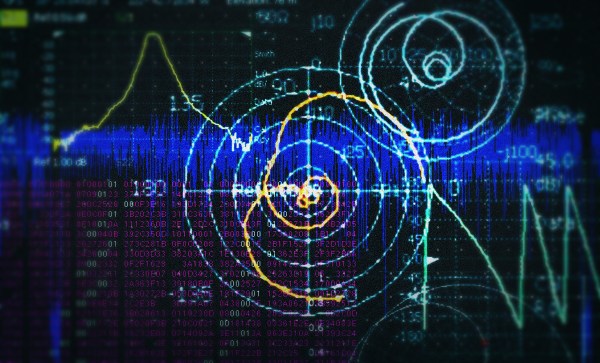

The spectrum analyzer feature is a crucial component of cable modems to help take advantage of the wide piece of spectrum that is available to them on the cable lines. With some of them it’s possible to access this feature directly by pointing a browser at it, but apparently some of them have a patch from the cable companies to limit access. By finding one that hasn’t had this patch applied it’s possible to access the spectrum analyzer, and once [kc9umr] attached some adapters and an antenna to his cable modem he was able to demonstrate it to great effect.

While it’s somewhat down to luck as to whether or not any given modem will grant access to this feature, for the ones that do it seems like a powerful and cheap tool. It’s agnostic to platform, so any computer on the network can access it easily, and compared to an RTL-SDR it has a wider range. There are some limitations, but for the price it can’t be beat which will cost under $50 in parts unless you happen to need two inputs like this analyzer .

Thanks to [Ezra] for the tip!