There is one man whose hour-long sessions in my company give me days of stress and worry. He can be found in a soundless and windowless room deep in the bowels of an anonymous building in a town on the outskirts of London. You’ve probably driven past it or others like it worldwide, without being aware of the sinister instruments that lie within.

The man in question is sometimes there to please the demands of the State, but there’s nothing too scary about him. Instead he’s an engineer and expert in electromagnetic compatibility, and the windowless room is a metal-walled and RF-proof EMC lab lined with ferrite tiles and conductive foam spikes. I’m there with the friend on whose work I lend a hand from time to time, and we’re about to discover whether all our efforts have been in vain as the piece of equipment over which we’ve toiled faces a battery of RF-related tests. As before when I’ve described working on products of this nature the specifics are subject to NDAs and in this case there is a strict no-cameras policy at the EMC lab, so yet again my apologies as any pictures and specifics will be generic.

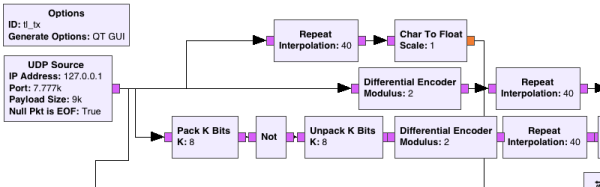

There are two broadly different sets of tests which our equipment will face: RF radiation, and RF injection. In simple terms: what RF does it emit, and what happens when you push RF into it through its connectors and cables? We’ll look at each in turn as a broad overview pitched at those who’ve never seen inside an EMC lab, sadly there simply isn’t enough space in a Hackaday article to cover every nuance.

Continue reading “An Overview Of The Dreaded EMC Tests” →

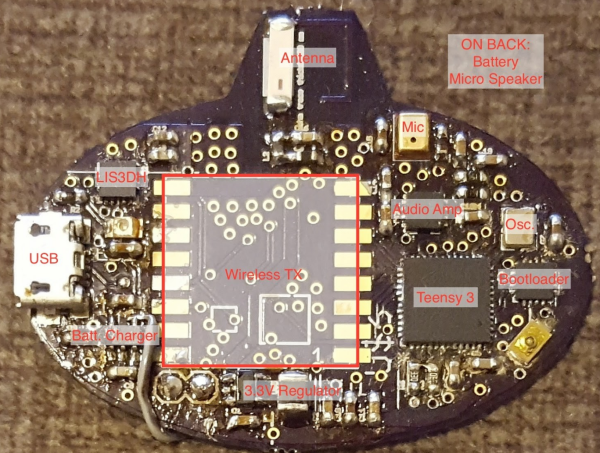

The first problem [Joe] dealt with was finding a radio which could run from watch batteries, and provide decently long-range operations. He chose the HopeRF RFM69HCW. Bringing fiction a bit closer to reality, this module has been used for

The first problem [Joe] dealt with was finding a radio which could run from watch batteries, and provide decently long-range operations. He chose the HopeRF RFM69HCW. Bringing fiction a bit closer to reality, this module has been used for