Professional mountain bike racing is a rather bizarre sport. At the highest level, times between podiums will be less than a second, and countless hours of training and engineering go into those fractions of seconds. An all too important tool for the world cup race team is data acquisition systems (DAQ). In the right hands, they can offer an unparalleled suspension tune for a world cup racer. Sadly DAQs can cost thousands of dollars, so [sghctoma] built one using little more then potentiometer and LEGO.

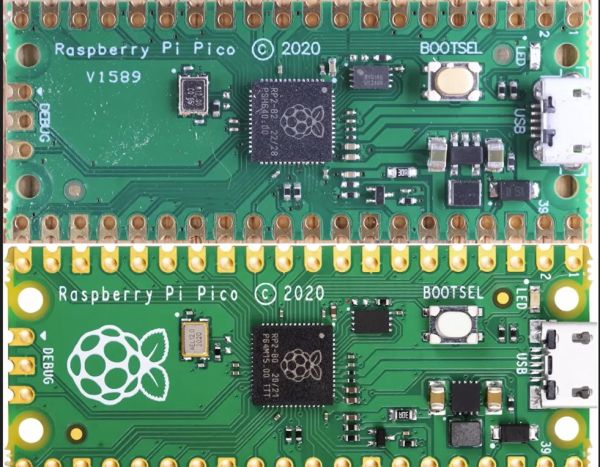

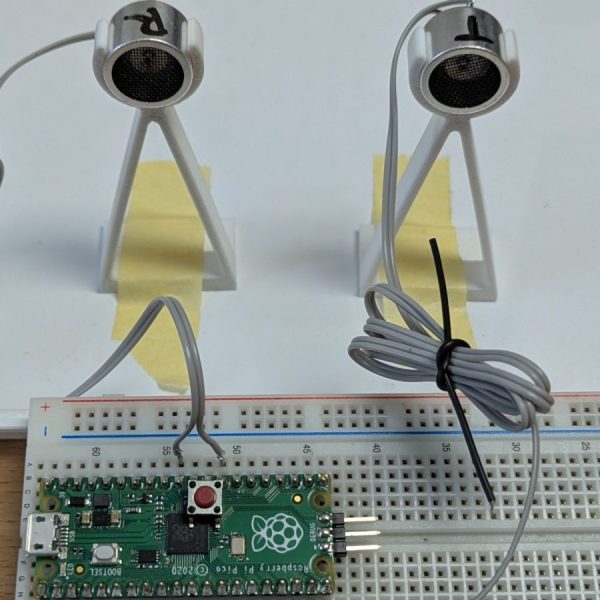

The hardware is a fairly simple task to solve. A simple Raspberry Pi Pico setup is used to capture potentiometer data. By some simple LEGO linkage and mounts, this data is correlated to the bikes’ wheel travel. Finally, everything is logged onto an SD card in a CSV format. Some buttons and a small AMOLED provide a simple user interface wrapped in a 3D printed case.

Continue reading “Making A Mountain Bike Data Acquisition System”