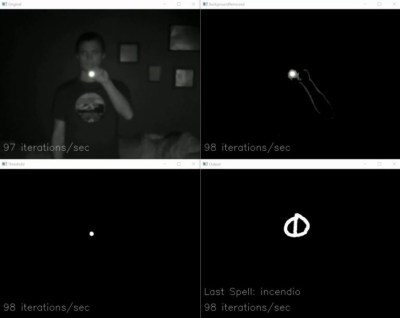

Never underestimate the quick and dirty hack. It’s very satisfying to rapidly solve a real problem with whatever you have on hand, and helps to keep your hacking skills sharp for those big beautifully engineered projects. [Guillaume M] needed a way to remotely open his apartment building door for deliveries, so he hacked the ancient intercom to be operated via Telegram, to allow packages to be deposited safely inside his mailbox inside the building’s front too.

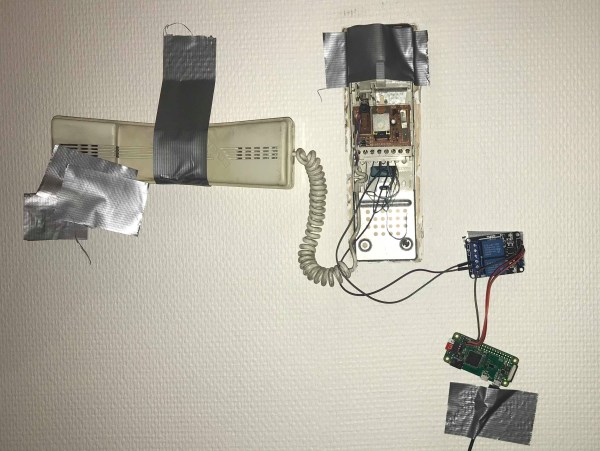

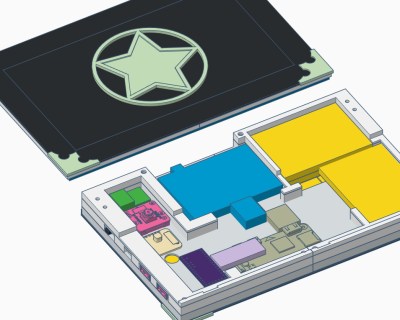

[Guillaume] needed to complete the hack in a way that would allow him to return the intercom to its original state when he moves out. Opening the 30-year-old unit, he probed a row of screw terminals and identified a 13V supply, ground, and the connection to the buildings’ door lock. He connected the lock terminals to a relay, which is controlled by a Raspberry Pi Zero W that waits for the “open” command to be sent to a custom Telegram Bot.

To power the Pi, [Guillaume] connected it to the 13V supply on the intercom via a voltage divider circuit. Voltage dividers usually make lousy power supplies, since the output voltage will fluctuate as the load changes, but it looks as though it worked well enough for [Guillaume]. The intercom had a lot of empty space inside, so after testing everything was packed inside the housing.

If you want to achieve the same with an ESP8266, there’s a library for that. Just keep in mind that being dependent on web servers to open critical doors might get you locked out.