Does anyone remember the Black Hat BCard hack in 2018? This hack has been documented extensively, most notoriously by [NinjaStyle] in his original blog post revealing the circumstances around discovering the vulnerability. The breach ended up revealing the names, email addresses, phone numbers, and personal details of every single conference attendee – an embarrassing leak from one of the world’s largest cybersecurity conferences.

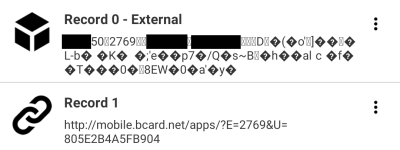

To recap: The Black Hat conference badges included an embedded NFC tag storing the participant’s contact details presumably for vendors to scan for marketing purposes. After scanning the tag, [NinjaStyle] realized that his name was readily available, but not his email address and other information. Instead, the NFC reader pointed to the BCard app – an application created for reading business cards.

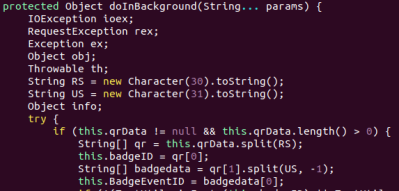

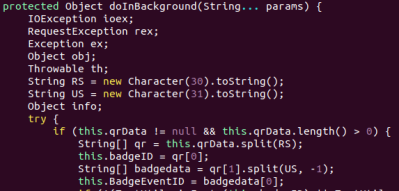

[NinjaStyle] decompiled the APK for the app to search for API endpoints and found that the participants each had a custom URL made using event identification values. After finding data that appeared to correspond to an eventID and badgeID, he sent a request over a web browser and found that his attendee data was returned completely unauthenticated. With this knowledge, it was possible to brute-force the contact details for every Black Hat attendee (the range of valid IDs was between 100000-999999, and there were about 18,000 attendees). Using Burp Suite, the task would take about six hours.

He was able to get ahold of BCard to reveal the vulnerability, which was fixed in less than a day by disabling the leaky API from their legacy system. Even so, legacy APIs in conference apps aren’t an uncommon occurrence – the 2018 RSA Conference (another cybersecurity conference) also suffered from an unprotected app that allowed 114 attendee records to be accessed without permission.

With the widespread publicity of leaked attendee data, event organizers are hopefully getting smarter about the apps that they use, especially if they come from a third-party vendor. [Yashvier Kosaraju] gave a talk at TROOPERS19 about pen testing several large vendors and discovering that Kitapps (Attendify) and Eventmobi both built apps with unauthenticated access to attendee data. It’s hard to say how many apps from previous years are still around, or whether or not the next event app you use will come with authentication – just remember to stay vigilant and to not give too much of your personal data away.

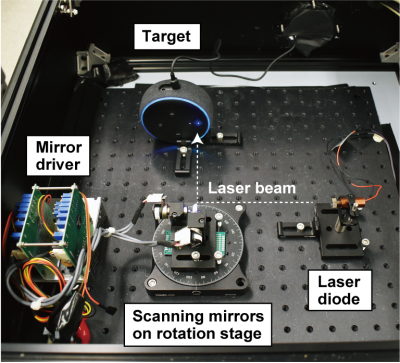

In one of the cooler hacks we’ve seen recently, a bunch of hacking academics at the University of Michigan researched the ability to flicker a laser at audible sound frequencies to see if they could remotely operate microphones simply by shining a light on them.

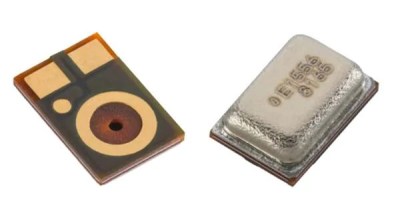

In one of the cooler hacks we’ve seen recently, a bunch of hacking academics at the University of Michigan researched the ability to flicker a laser at audible sound frequencies to see if they could remotely operate microphones simply by shining a light on them.  Knowles SPV0842LR5H. This attack is relatively easy to prevent; manufacturers would simply need to install screens to prevent light from hitting the microphones. For devices already installed in our homes, we recommend either putting a cardboard box over them or moving them away from windows where unscrupulous neighbors or KGB agents could gain access. This does make us wonder if MEMS mics are also vulnerable to radio waves.

Knowles SPV0842LR5H. This attack is relatively easy to prevent; manufacturers would simply need to install screens to prevent light from hitting the microphones. For devices already installed in our homes, we recommend either putting a cardboard box over them or moving them away from windows where unscrupulous neighbors or KGB agents could gain access. This does make us wonder if MEMS mics are also vulnerable to radio waves.