Looking for a unique vacation spot? Have at least $10 million USD burning a hole in your pocket? If so, then you’re just the sort of customer the rather suspiciously named “GRU Space” is looking for. They’re currently taking non-refundable $1,000 deposits from individuals looking to stay at their currently non-existent hotel on the lunar surface. They don’t expect you’ll be able to check in until at least the early 2030s, and the $1K doesn’t actually guarantee you’ll be selected as one of the guests who will be required to cough up the final eight-figure ticket price before liftoff, but at least admission into the history books is free with your stay.

The whole idea reminds us of Mars One, which promised to send the first group of colonists to the Red Planet by 2024. They went bankrupt in 2019 after collecting ~$100 deposits from more than 4,000 applicants, and we probably don’t have to tell you that they never actually shot anyone into space. Admittedly, the Moon is a far more attainable goal, and the commercial space industry has made enormous strides in the decade since Mars One started taking applications. But we’re still not holding our breath that GRU Space will be leaving any mints on pillows at one-sixth gravity.

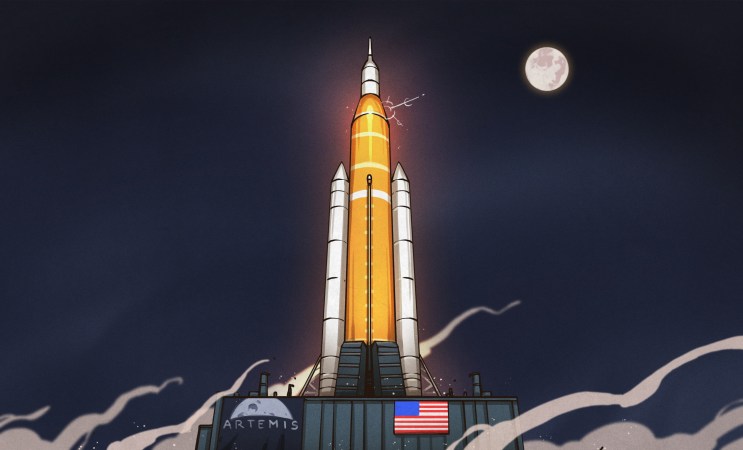

Speaking of something which actually does have a chance of reaching the Moon on time — on Saturday, NASA rolled out the massive Space Launch System (SLS) rocket that will carry a crew of four towards our nearest celestial neighbor during the Artemis II mission. There’s still plenty of prep work to do, including a dress rehearsal that’s set to take place in the next couple of weeks, but we’re getting very close. Artemis II won’t actually land on the Moon, instead performing a lunar flyby, but it will still be the first time we’ve sent humans beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) since Apollo 17 in 1972. We can’t wait for some 4K Earthrise video.