At Hackaday, we see community-driven open source development as the great equalizer. Whether it’s hardware or software — if there’s some megacorp out there trying to sell you something, you should have the option to go with a comparable open source version. Even if the commercial offering is objectively superior, it’s important that open source alternatives always exist, or else its the users themselves that end up becoming the product before too long.

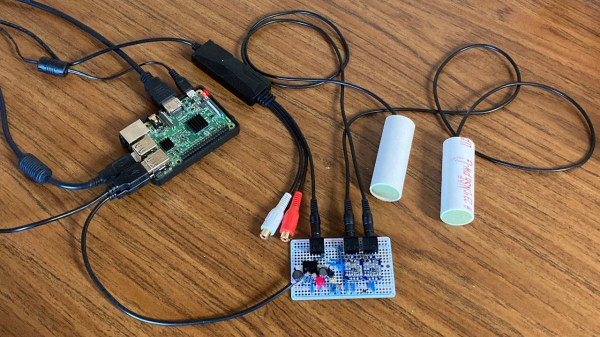

So we were particularly excited when [Neumi] wrote in to share his Open Echo project, as it contains some very impressive work towards democratizing the use of sonar. Over the years we’ve seen a handful of underwater projects utilize sonar in some form or another, but they have always simply read the data from a commercial, and generally expensive, unit. But Open Echo promises to delete the middle-man, allowing for cheaper and more flexible access to bathymetric data.

Continue reading “Setting The Stage For Open Source Sonar Development”