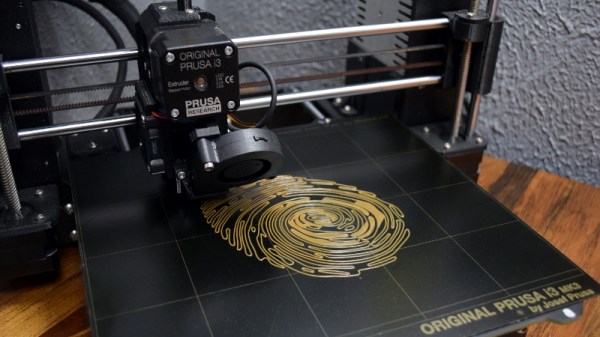

Hackers and makers see the desktop 3D printer as something close to a dream come true, a device that enables automated small-scale manufacturing for a few hundred dollars. But it’s not unreasonable to say that most of us are idealists; we see the rise of 3D printing as a positive development because we have positive intentions for the technology. But what of those who would use 3D printers to produce objects of more questionable intent?

We’ve already seen 3D printed credit card skimmers in the wild, and if you have a clear enough picture of a key its been demonstrated that you can print a functional copy. Following this logic, it’s reasonable to conclude that the forensic identification of 3D printed objects could one day become a valuable tool for law enforcement. If a printed credit card skimmer is recovered by authorities, being able to tell how and when it was printed could provide valuable clues as to who put it there.

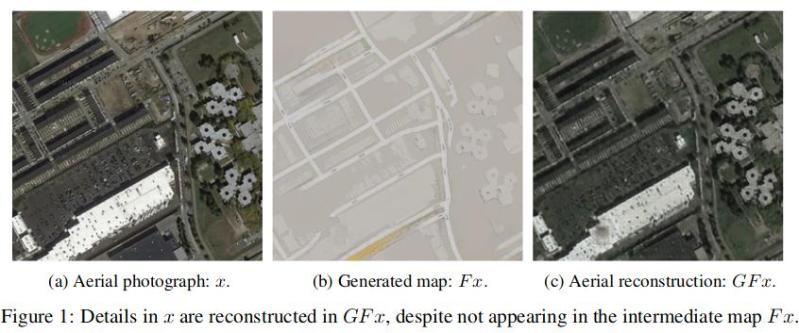

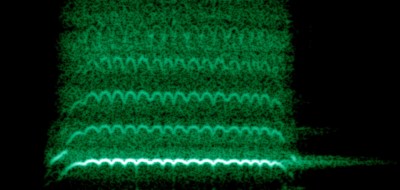

This precise line of thinking is how the paper “PrinTracker: Fingerprinting 3D Printers using Commodity Scanners” (PDF link) came to be. This research, led by the University at Buffalo, aims to develop a system which would allow investigators to scan a 3D printed object recovered from a crime scene and identify which printer was used to produce it. The document claims that microscopic inconsistencies in the object are distinctive enough that they’re analogous to the human fingerprint.

But like many of you, I had considerable doubts about this proposal when it was recently featured here on Hackaday. Those of us who use 3D printers on a regular basis know how many variables are involved in getting consistent prints, and how introducing even the smallest change can have a huge impact on the final product. The idea that a visual inspection could make any useful identification with all of these parameters in play was exceptionally difficult to believe.

In light of my own doubts, and some of the excellent points brought up by reader comments, I thought a closer examination of the PrinTracker concept was in order. How exactly is this identification system supposed to work? How well does it adapt to the highly dynamic nature of 3D printing? But perhaps most importantly, could these techniques really be trusted in a criminal investigation?

Continue reading “No, Your 3D Printer Doesn’t Have A Fingerprint” →