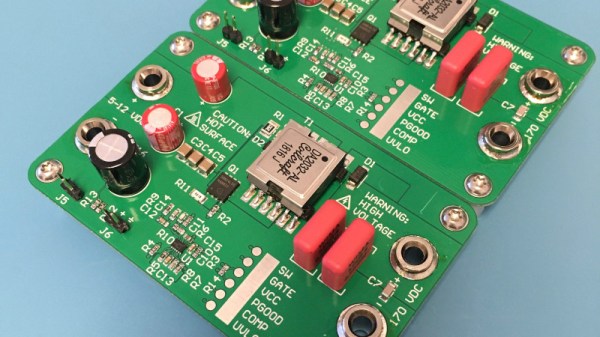

For as versatile and inexpensive as switch-mode power supplies are at all kinds of different tasks, they’re not always the ideal choice for every DC-DC circuit. Although they can do almost any job in this arena, they tend to have high parts counts, higher complexity, and higher cost than some alternatives. [Jasper] set out to test some alternative linear chargers called low dropout regulators (LDOs) for small-scale charging of lithium ion capacitors against those more traditional switch-mode options.

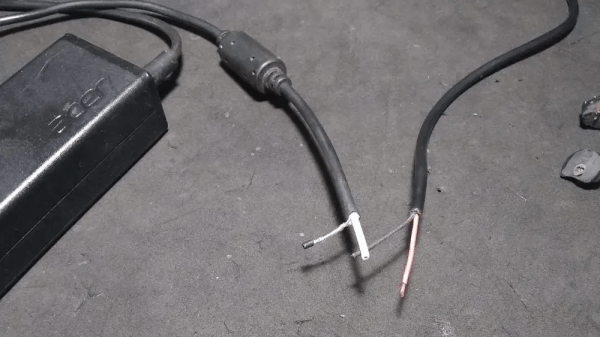

The application here is specifically very small solar cells in outdoor applications, which are charging lithium ion capacitors instead of batteries. These capacitors have a number of benefits over batteries including a higher number of discharge-recharge cycles and a greater tolerance of temperature extremes, so they can be better off in outdoor installations like these. [Jasper]’s findings with using these generally hold that it’s a better value to install a slightly larger solar cell and use the LDO regulator rather than using a smaller cell and a more expensive switch-mode regulator. The key, though, is to size the LDO so that the voltage of the input is very close to the voltage of the output, which will minimize losses.

With unlimited time or money, good design can become less of an issue. In this case, however, saving a few percentage points in efficiency may not be worth the added cost and complexity of a slightly more efficient circuit, especially if the application will be scaled up for mass production. If switched mode really is required for some specific application, though, be sure to design one that’s not terribly noisy.