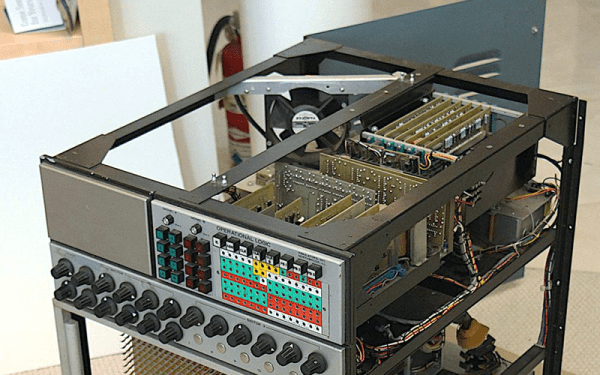

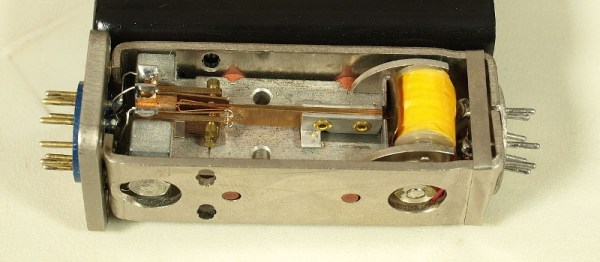

The switch-mode power supply has displaced traditional supplies almost completely over the last few decades, being smaller, lighter, and more efficient. But that’s not to say that it’s a new idea, and on the way to today’s high-frequency devices there have been quite a few steps. An earlier one is the subject of a teardown video from [Thomas Scherrer OZ2CPU], as he takes a look at a 1960s HP power supply with a slightly different approach to regulation for the day. Instead of a linear regulator on its conventional transformer and rectifier circuit, it has a pair of SCRs in the mains supply that chop at mains frequency. It’s a switch mode supply, but not quite as you’re used to.

In fact, these circuits using an SCR or a triac weren’t quite as uncommon as you might expect, and could at one point be found in almost every domestic TV set or light dimmer. Sometimes referred to as “chopper” supplies, they represented a relatively cheap way to derive a regulated DC voltage from an AC mains source in the days before anyone cared too much about RF emissions, and though few were as high quality as the HP shown in the video below, they were pretty reliable.

If older switchers interest you, this is not the first one we’ve shown you from that era.

] rounds out this week’s Hacklet with his

] rounds out this week’s Hacklet with his