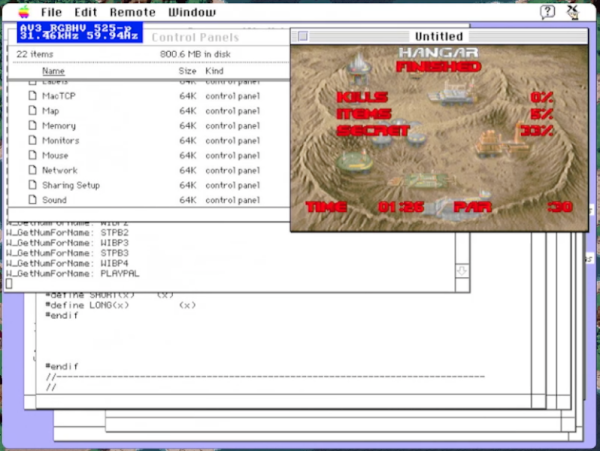

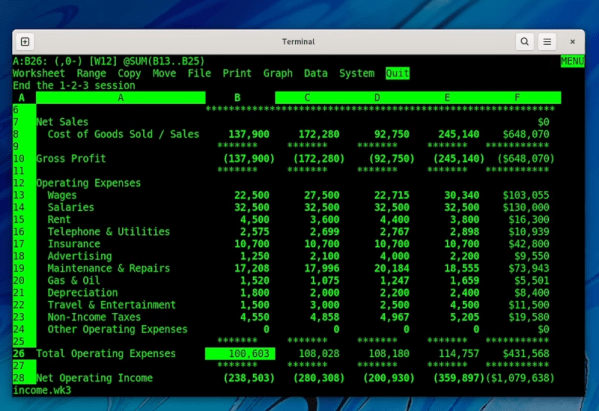

Ever hear of Lotus 123? It is an old spreadsheet program that dominated the early PC market, taking the crown from incumbent Visicalc. [Tavis Ormandy] has managed to get the old software running natively under Linux — quite a feat for software that is around 40 years old and was meant for a different operating system. You can see the results in glorious green text on a black screen in the video below.

If you are a recent convert to Linux, you might not remember what a pain it was “in the old days” to install software. But in this case, it is even worse since the software isn’t even for Linux. The whole adventure started with [Tavis] wanting to find the API kit used to add plugins to Lotus. In theory, you could use it to add modern features to the venerable spreadsheet program.

The $395 software development kit wasn’t very common and there was also a Unix version of Lotus 123, but no one seemed to have a copy of that. [Tavis] eventually found someone who ran a circa-1990 BBS and had the data on tape. Turned out there was a hot copy of the SDK that he was able to use. But he noticed something else in the BBS’s list of files: the long-lost Unix version of Lotus!

An investigation found the installer used TD0 files which took some research. Luckily, a utility exists that can convert these to raw disk images. Inside was a very large object file. Apparently, in the days without dynamic loading, that object would be linked with plug in modules to install them.

The object file had all of its debugging information intact which shed a lot of light on the program’s internal operations. The old executables used COFF format but it is possible to relink it to an ELF file. Of course, it isn’t just that easy. [Tavis] wrote a small program to remove the old-style Unix system calls so they could be rerouted to Linux system calls. Some calls just pass through, but others need some translation due to differences in things like structure layout, sizes, and alignment.

In the end, it all worked but didn’t have a valid license. However, [Tavis] felt like since he did have a license and the software is abandoned, he was within his rights to crack the license check.

We are well-known abusers of spreadsheets around here. Of course, we aren’t the only ones.

Continue reading “Lotus 123 For Linux Is Like A Digital Treasure Hunt” →