Few things rival the usability and speed of a full-sized keyboard for text input. For decades, though, keyboards were mostly wired, which can limit where you use your favorite one. To address this, [KoStard]’s latest project uses an ESP32 to bridge a USB keyboard to BLE devices.

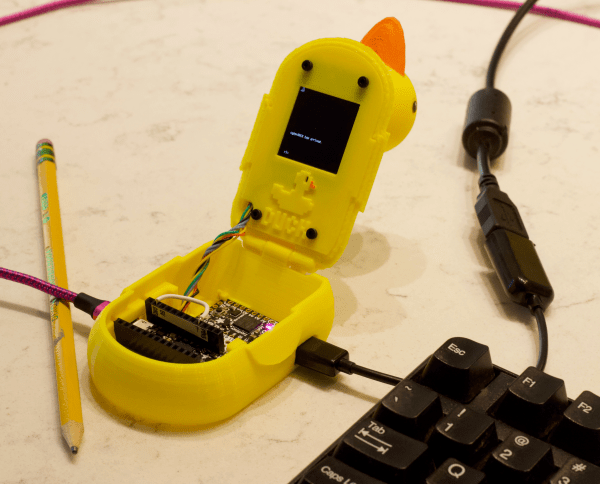

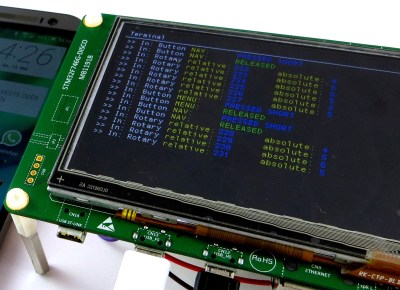

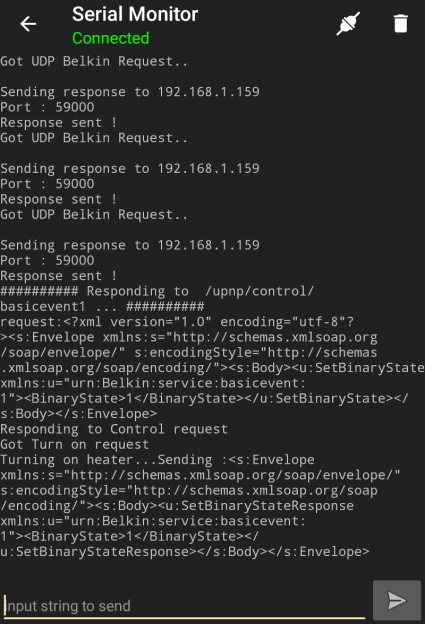

The ESP32-S3 packs a ton of fantastic functionality into its small size and low price—including USB-OTG support, which is key here. Taking advantage of this, [KoStard] programmed an ESP32-S3 to host a keyboard over its USB port while connecting via BLE to devices like cellphones.

There are some slick tricks baked in, too: you can pair with up to three devices and switch between them using a key combo. Some of you might be wondering how you can just plug a microcontroller into a keyboard and have it work. The truth is, it doesn’t without extra hardware. Both the keyboard and ESP32-S3 need power. The simplest fix is a powered USB hub: it can be battery-powered for a truly mobile setup, or use a wired 5V supply so you never have to charge batteries.

We love seeing a simple, affordable microcontroller extend the usefulness of gear you already have. Let us know in the comments about other hacks you’ve used to connect keyboards to devices never designed for them.

Continue reading “Wired To Wireless: ESP32 Gives Your USB Keyboard Bluetooth”