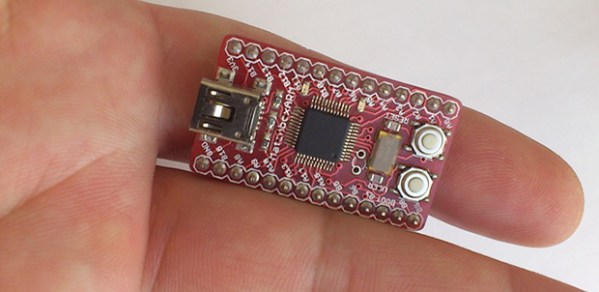

[George and Bogdan] wrote in to tell us about a cool Kickstarter they’ve been working on. It’s called the MatchboxARM, and like other tiny-yet-powerful ARM dev boards floating around, this one features a very fast and capable processor and more than enough pins for just about any project. One interesting feature of this board, however, makes it stand out from the pack: it has a USB mass storage-based bootloader, meaning uploading new code is as easy as a drag and drop.

This isn’t the first dev board we’ve seen to sport this feature: the Stellaris Launchpad has had this for a while and even the lowly ATtiny85, in the form of a Digispark has a mass storage-based bootloader. The MatchboxARM, though, brings this together with a very powerful ARM microcontroller with enough I/Os, ADCs, PWM pins, and I2C and SPI ports for the most complicated projects.