The image of the crackpot inventor, disheveled, disorganized, and surrounded by the remains of his failures, is an enduring Hollywood trope. While a simple look around one’s shop will probably reveal how such stereotypes get started, the image is largely not a fair characterization of the creative mind and how it works, and does not properly respect those who struggle daily to push the state of the art into uncharted territory.

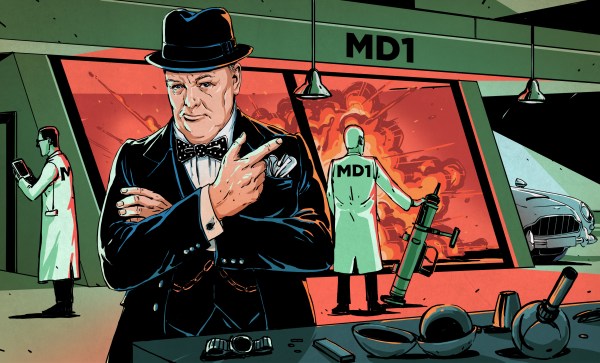

That said, there are plenty of wacky ideas that have come down the pike, most of which mercifully fade away before attracting undue attention. In times of war, though, the need for new and better ways to blow each other up tends to bring out the really nutty ideas and lower the barrier to revealing them publically, or at least to military officials.

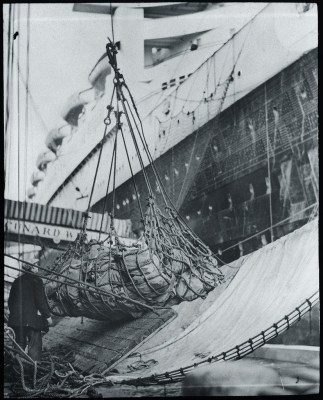

Of all the zany plans that came from the fertile minds on each side of World War II, few seem as out there as a plan to use birds to pilot bombs to their targets. And yet such a plan was not only actively developed, it came from the fertile mind of one of the 20th century’s most brilliant psychologists, and very nearly resulted in a fieldable weapon that would let fly the birds of war.

Continue reading “Hacking When It Counts: Pigeon-Guided Missiles”