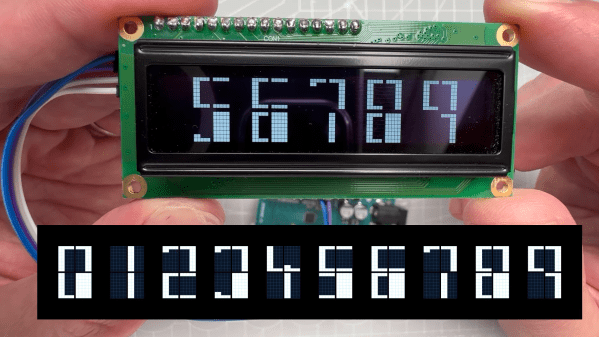

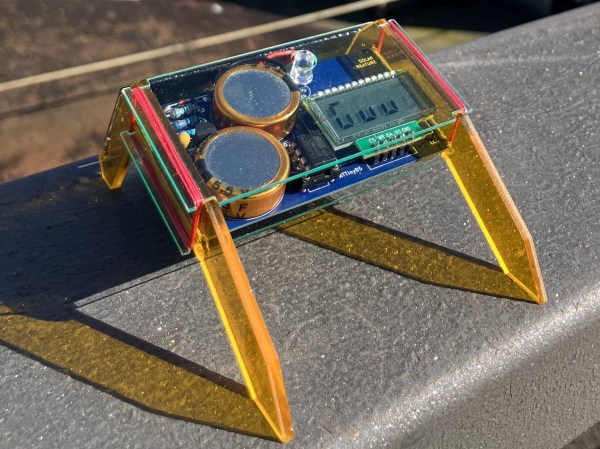

Liquid crystal and Organic LED displays have revolutionized portable computing. They’re also made of glass. Which presents a problem: How do we get electrical signals from fiberglass circuit boards to the glass displays? The answer is double-sided adhesive tape. But we’re not talking about packing tape here. As [Breakingtaps] explains, this tape has a trick up its sleeve.

The magic is that the tape conducts only in the vertical plane. Even more so, any two conducting sections of the tape are insulated from each other. How does it do that? Magic beans balls, of course!

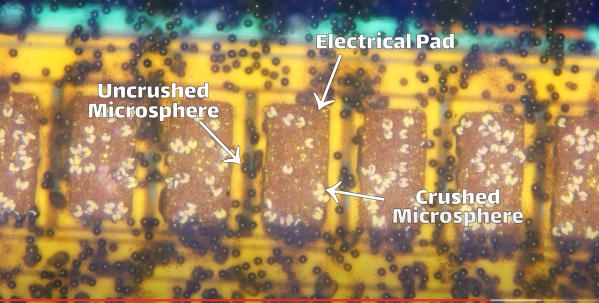

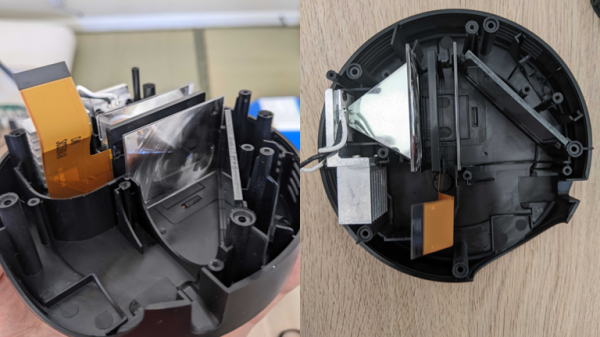

The tape and adhesive are insulators. Embedded in the adhesive are tiny spheres. The spheres are made of plastic and coated with metal. When the tape (also known as ACF or Anisotropic Conductive Film) is pressed between a PCB with conductors and glass, a few spheres are squished down between the layers. Electrical signals pass between the squished spheres, allowing an image to be displayed on the glass screen. The final step uses heat and pressure to bond the adhesive and cure it. You can also get the material in paste form if you don’t like the tape.

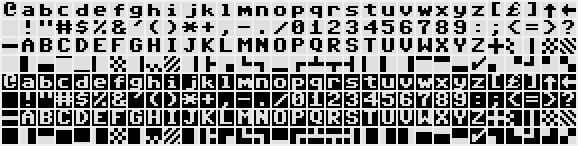

The system works so well that it can be used for connections from a silicon chip directly to the glass. This is how many display controllers are mounted right to the module — definitely an improvement on the rubber strips used on LCDs of the past.