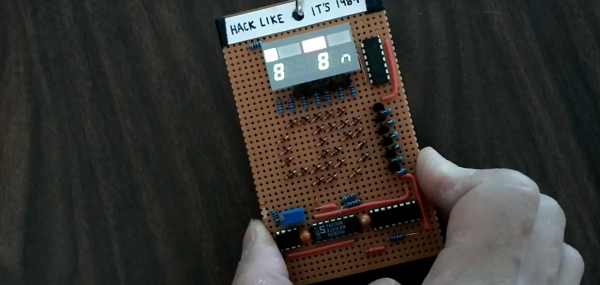

DEF CON 25’s theme was retro-tech, and [xres0nance] wasn’t kidding around in the retro badge he built for the convention. The badge was mostly built out of actual parts from the ’80s and ’90s, including the perfboard from Radio Shack—even the wire and solder. Of the whole project just the resistors and 555 were modern parts, and that’s only because [xres0nance] ran out of time.

[xres0nance] delayed working on the badge until his flight, throwing the parts in a box, and staggering to the airport in the midst of a “three-alarm hangover”. He designed the badge on the plane, downloading datasheets over in-flight WiFi and sketching out circuits in his notebook.

The display is from an old cell phone, and it uses a matrix of diodes to spell out DEFCON without the help of a microcontroller. Each letter is powered by a transistor, with specific pins blocked out to selectively power the segments. He used a shift register timed by a 555 to trigger each letter in turn, with the display scrolling the resulting message.

We publish a lot of posts about con badges. See our DEF CON 2015 badge summary for a bunch of badges that we encountered at in Vegas.