In the distant past, engineers used exotic devices to measure orientation, such as large mechanical gyros and mercury tilt switches. These are all still useful methods, but for many applications MEMS motions devices have become the gold standard. When [g199] set out to build their Balance Box game, it was no exception.

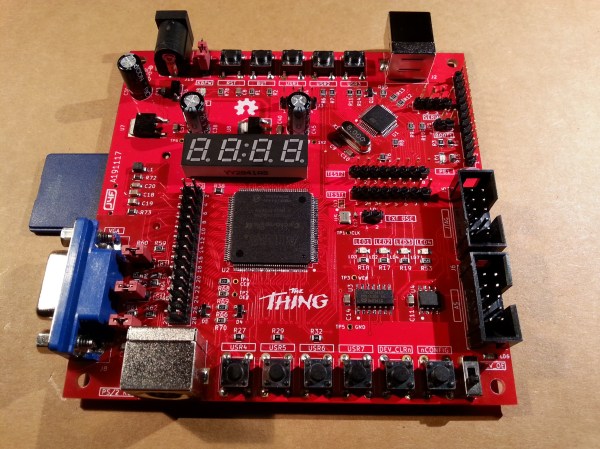

The game consists of a plastic box, upon which a spirit level is fitted, along with a series of LEDs. The aim of the game is to keep the box level while carrying it to a set goal. Inside, an Arduino Uno monitors the output of a MPU 6050, a combined accelerometer and gyroscope chip. If the Arduino detects the box is tilting, it warns the user with the LEDs. Tilt it too far, and a life is lost. When all three lives are gone, the game is over.

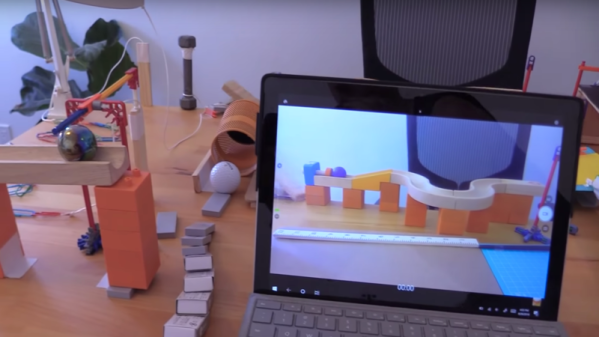

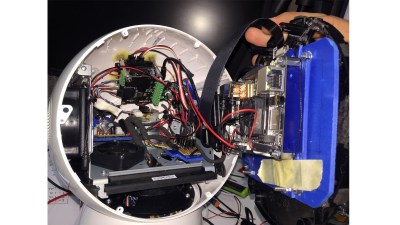

It’s a cheap and simple build that would have been inordinately more expensive only 10 to 20 years ago. It goes to show the applications enabled by ubiquitous cheap electronics like MEMS sensors. The technology has other fun applications, too – for example the Stecchino game, or this giant balance board joystick. We’re certainly lucky to have such powerful technology at our fingertips!