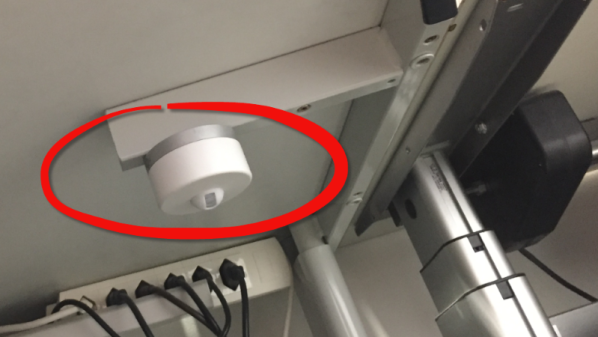

There’s nothing wrong with building something just to build it, but there’s something especially satisfying about being able to solve a real-world problem with a piece of gear you’ve designed and fabricated. When all the traditional methods to keep birds from roosting on his mother’s property failed, [MNMakerMan] decided to come up with a more persuasive option: a solar powered spinning owl complete with expandable batons.

We imagine the owl isn’t strictly necessary when you’re whacking the birds with a metal bar to begin with, but it does add a nice touch. Perhaps it will even serve to deter some of the less adventurous birds before they get within clobbering distance, which is probably in their best interest. [MNMakerMan] says the rotation speed of the bars seems low enough that he doesn’t think it will do the birds any physical harm, but it’s still got to be fairly unpleasant.

We imagine the owl isn’t strictly necessary when you’re whacking the birds with a metal bar to begin with, but it does add a nice touch. Perhaps it will even serve to deter some of the less adventurous birds before they get within clobbering distance, which is probably in their best interest. [MNMakerMan] says the rotation speed of the bars seems low enough that he doesn’t think it will do the birds any physical harm, but it’s still got to be fairly unpleasant.

At first glance you might think that this contraption simply spins when the small 10 watt photovoltaic panel next to it catches the sun, but there’s actually a bit more to it than that. Sure he probably could just have it spin constantly whenever the sun is up, but instead [MNMakerMan] is using a ATtiny85 to control the 11 RPM geared DC motor with a IRF540 MOSFET. By adding a DS3231 RTC module into the mix, he’s able to not only accurately control when the spinner begins and ends its bird-busting shift, but implement timed patterns rather than running it the whole time. All of which can of course be fine-tuned by adjusting a couple variables and reflashing the chip.

We’ve seen plenty of automated systems for keeping cats away, and of course squirrels are a common target for such builds as well, but devices to deter birds are considerably less common among these pages. So it would seem that, at least for now, [MNMakerMan] has the market cornered on solar bird smashing gadgets. We’re sure Mom’s very proud.

Continue reading “Keeping Birds At Bay With An Automated Spinning Owl”