We always thought the older console games looked way better back in the day on old CRTs than now on a modern digital display. [Stephen Walters] thinks so too, and goes into extensive detail in a lengthy YouTube video about the pros and cons of CRT vs digital, which was totally worth an hour of our time. But are CRTs necessary for retro gaming?

The story starts with [Stephen] trying to score a decent CRT from the usual avenue and failing to find anything worth looking at. The first taste of a CRT display came for free. Left looking lonely at the roadside, [Stephen] spotted it whilst driving home. This was a tiny 13″ Sanyo DS13320, which, when tested, looked disappointing, with a blurry image and missing edges. Later, they acquired a few more displays: a Pansonic PV-C2060, an Emerson EWF2004A and a splendid-looking Sony KV24FS120. Some were inadequate in various ways, lacking stereo sound and component input options.

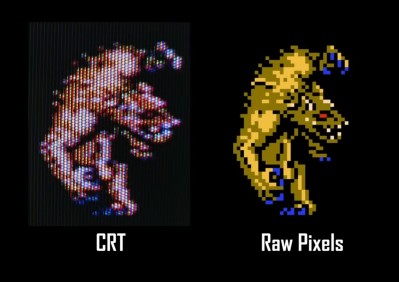

A large video section discusses the reasons for the early TV standards. US displays (and many others using NTSC) were designed for 525 scan lines, of which 480 were generally visible. These displays were interlaced, drawing alternating fields of odd and even line numbers, and early TV programs and NTSC DVDs were formatted in this fashion. Early gaming consoles such as the NES and SNES, however, were intended for 240p (‘p’ for progressive) content, which means they do not interlace and send out a blank line every other scan line. [Stephen] goes into extensive detail about how 240p content was never intended to be viewed on a modern, sharp display but was intended to be filtered by the analogue nature of the CRT, or at least its less-than-ideal connectivity. Specific titles even used dithering to create the illusion of smooth gradients, which honestly look terrible on a pixel-sharp digital display. We know the differences in signal bandwidth and distortion of the various analog connection standards affect the visuals. Though RGB and component video may be the top two standards for quality, games were likely intended to be viewed via the cheaper and more common composite cable route.