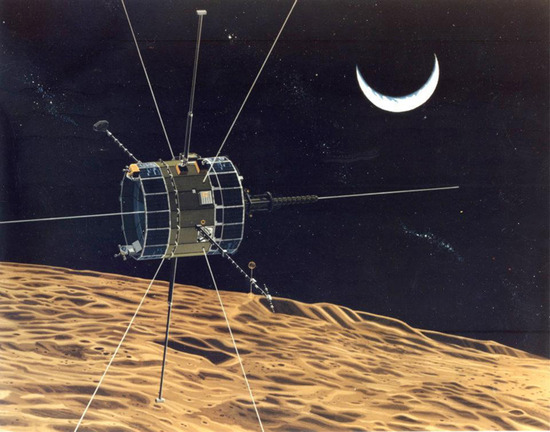

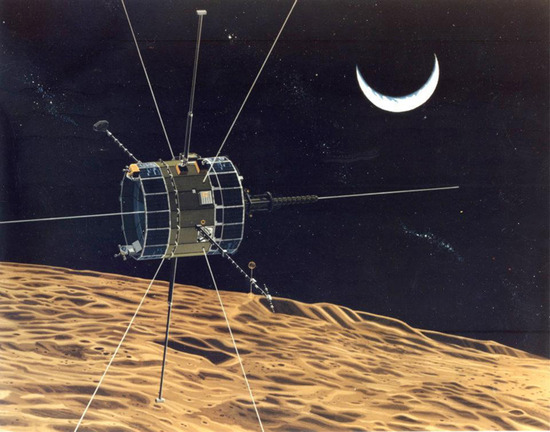

The mission to save ISEE-3 has is underway. The ISEE-3 Reboot Project has posted a crowdfunding campaign on Rockethub. When we first covered the ISEE-3 story no one had heard from it since 2008. Since then AMSAT-DL, an amateur radio group in Germany has received signals from the probe.

The ISEE-3 Reboot Project is being managed by [Dennis Wingo] and [Keith Cowing], the same two men who spearheaded the effort to recover NASA’s Lunar Orbiter images from old magnetic tapes. They did most of their work using restored 1960’s equipment in a vacant McDonald’s.

The goal of the ISEE Reboot Project is to return ISEE-3 to its original Earth/Sun Lagrange point L1 orbit. Once safely back in orbit, it will be used for STEM education, amateur radio solar predictions, and for science about the sun. In [Dennis Wingo’s] own words

If we can do this, we will have an open source, publicly accessible satellite data stream of the first open source satellite above Low Earth Orbit.

[Wingo] and [Cowing] aren’t alone in this effort; they are working with a venerable dream team. In addition to getting the nod from NASA, the team also has the help of [Dr. Robert Farquhar], the orbital dynamics guru who originally designed ISEE-3’s comet intercept orbit . [Farquhar] has an extremely personal reason to participate in this project. In 1982 he “borrowed” the satellite to go comet hunting. Once that mission was complete, he promised to give ISEE-3 back. [Dr. Farquhar] and his team designed the maneuvers required to bring ISEE-3 back to L1 orbit back in the 1980’s. This includes a breathtaking moon flyby at an altitude of less than 50 km. Seriously, we want to see this guy’s KSP missions.

Communicating with the ISEE-3 is going to take some serious power and antenna gain. The project has this in the form of a 21 meter dish at Moorehead State University in Kentucky, USA, and the Arecibo Observatory. Arecibo should be well-known to our readers by now. Moorehead and Arecibo have both received signals from ISEE-3. The reboot project team is also working directly with the AMSAT-DL team in Germany.

If this effort seems a bit rushed, that’s because time is very short. To implement [Dr. Farquhar’s] plan, ISEE-3 must fire its thrusters by late June 2014. In just two months the team needs to create software to implement ISEE-3’s communications protocols, obtain and install transmitters at Moorehead and Aricibo, and send some basic commands to the craft. Only then can they begin to ascertain ISEE-3’s overall health in preparation for a thruster burn.

If the ISEE-3 Reboot Project succeeds, we’ll have an accessible satellite well outside of low Earth orbit. If it fails, Issac Newton will remain at the helm. ISEE-3 will fly right past Earth, not to be seen again until August 2029.

Continue reading “ISEE-3 Dream Team Needs Your Help” →