If you have OCD, then the worst thing someone could do is give you a bowl of multi-coloured M&M’s or Skittles — or Gems if you’re in the part of the world where this was written. The candies just won’t taste good until you’ve managed to sort them in to separate coloured heaps. And if you’re a hacker, you’ll obviously build a sorting machine to do the job for you.

Use our search box and you’ll find a long list of coverage describing all manner and kinds of sorting machines. And while all of them do their designated job, 19 year old [Willem Pennings]’s m&m and Skittle Sorting Machine is the bees knees. It’s one of the best builds we’ve seen to date, looking more like a Scandinavian Appliance than a DIY hack. He’s ratcheted up a 100k views on Youtube, 900k views on imgur and almost 2.5k comments on reddit, all within a day of posting the build details on his blog.

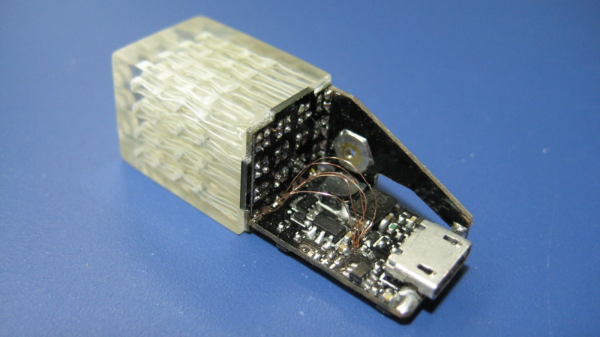

As quite often happens, his work is based on an earlier design, but he ends up adding lots of improvements to his version. It’s got a hopper at the top for loading either m&m’s or Skittles and six bowls at the bottom to receive the color sorted candies. The user interface is just two buttons — one to select between the two candy types and another to start the sorting. The hardware is all 3D printed and laser cut. But he’s put in extra effort to clean the laser cut pieces and paint them white to give it that neat, appliance look. The white, 3D printed parts add to the appeal.

Rotating the input funnel to prevent the candies from clogging the feed pipes is an ace idea. A WS2812 LED is placed above each bowl, lighting up the bowl where the next candy will be ejected and at the same time, a WS2812 strip around the periphery of the main body lights up with the color of the detected candy, making it a treat, literally, to watch this thing in action. His blog post has more details about the build, and the video after the break shows the awesome machine in action.

And if you’re interested in checking out how this sorter compares with some of the others, check out these builds — Skittles sorting machine sorts Skittles and keeps the band happy, Anti-Entropy Machine Satiates M&M OCD, Only Eat Red Skittles? We’ve Got You Covered, and Hate Blue M&M’s? Sort Them Using the Power of an iPhone! As we mentioned earlier, candy sorting machines are top priority for hackers.

Continue reading “M&Ms And Skittles Sorting Machine Is Both Entertainment And Utility”

[Bjørn Karmann]’s

[Bjørn Karmann]’s