Open-source technology brings a world that laws and regulations are not quite prepared for. As a result, every now and then, open projects need to work around governmental regulations. In today’s news, KrakenRF team has stumbled into an arms-trafficing legal roadblock for their KrakenSDR-based passive radar code, and is currently figuring it out. There’s no indication that there’s been any legal action from the USA government – the team’s being proactive, as fas as we’re told.

KrakenSDR hardware, to simplify it a lot, is five RTL-SDRs on one PCB – with plenty of work put in to do it the right way. It gets you much further than a few dongles – there’s shielded case, suitable connectors, reliable power distribution, a proper USB hub, and importantly, receiver synchronization hardware. Naturally, there’s nice things you can build with such a hefty package – one of them is passive radar, which was a prominent selling point on both KrakenSDR’s pre-launch page back in 2021, and on their crowdfunding page just a week ago. How does that work?

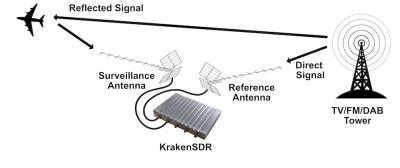

There’s RF emissions floating around you in the air, unless you’re at sea or in the desert. Whether it’s airplane transponders, cell towers, or a crappy switch-mode PSU, the radiowaves emitted interact with objects all around you. If you have multiple receivers with directional antennas, you can catch waves being reflected from some object, compare the wave reflected wave to the wave received from the initial source, and determine the object’s properties like location and speed. If you’d like to know more, IEEE Spectrum has covered this topic just a week ago, and the previously-deleted KrakenSDR wiki page has more details for you to learn from.

There’s RF emissions floating around you in the air, unless you’re at sea or in the desert. Whether it’s airplane transponders, cell towers, or a crappy switch-mode PSU, the radiowaves emitted interact with objects all around you. If you have multiple receivers with directional antennas, you can catch waves being reflected from some object, compare the wave reflected wave to the wave received from the initial source, and determine the object’s properties like location and speed. If you’d like to know more, IEEE Spectrum has covered this topic just a week ago, and the previously-deleted KrakenSDR wiki page has more details for you to learn from.

Through exposure in IEEE Spectrum, the KrakenSDR work has received plenty of attention and comments. And this is where the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) laws come in. We’re not lawyers, but it does look like passive radar is on the list. Today, the code repository and the documentation pages are scrubbed clean while the team is talking to legal experts.

Dealing with this is intimidating, and we wish them luck in clearing this with legal. In the bad old days, certain encryption algorithms were famously in scope, which appeared absolutely ridiculous to us at the time. The laws did eventually change to better reflect reality, but the wheels of justice turn slowly.

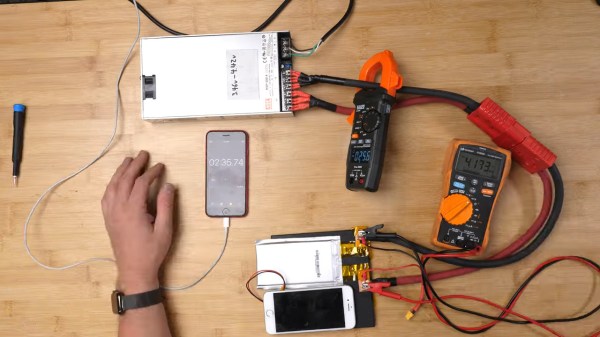

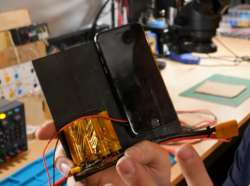

What people commonly encounter is that charging speed depends on the charger involved, but even one hundred chargers in parallel won’t speed up this iPhone’s charging rate, so what’s up? First off, the phone’s charger chip and the battery’s BMS will both limit charging current, so for experiment purposes, those had to be bypassed. First attempt was using a hefty DC power supply with the original cell, and, unsatisfied with the lack of fire and still relatively slow charging, [Scotty] decides to up the ante.

What people commonly encounter is that charging speed depends on the charger involved, but even one hundred chargers in parallel won’t speed up this iPhone’s charging rate, so what’s up? First off, the phone’s charger chip and the battery’s BMS will both limit charging current, so for experiment purposes, those had to be bypassed. First attempt was using a hefty DC power supply with the original cell, and, unsatisfied with the lack of fire and still relatively slow charging, [Scotty] decides to up the ante.