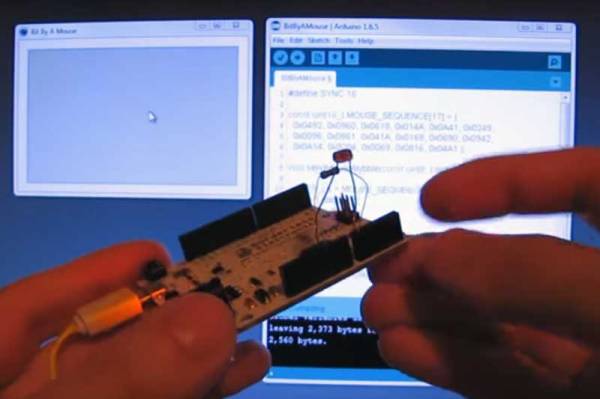

[Ido Gendel] was thinking about new and interesting ways to send data between devices, when he realized that the answer was right in his hand. Literally: he decided to try sending data using the mouse pointer. What he came up with was an interesting hack that uses small movements of the mouse pointer to send data at up to 1200bps, or about 150 bytes per second.

The way he did this was very, very clever. He used an Arduino Leonardo that is set to emulate a mouse, working alongside his existing mouse. This setup means that he can use his existing mouse: the system just sees the Arduino as a second mouse, and the pointer just looks a little jerky when you zoom in. That is because the Arduino is just sending tiny movements, each of which is a code that represents a nybble (4 binary bits) of data. By using both a combination of three left-right or up-down movements, he was able to create 16 movements, each of which can encode 4 bits of data. Each of these encoding movements also returns the mouse to its origin point, so the mouse doesn’t mysteriously scroll off the screen when data is being sent.