[Paul Brown] wants to take advantage of off-site server colocation services. But the providers within [Paul]’s region typically place a limit of 1A @ 120V on each server. Rather than search out commercial low-power solutions, [Paul] embraced the hacker spirit and built his own server from five Raspberry Pi 4b single board computers.

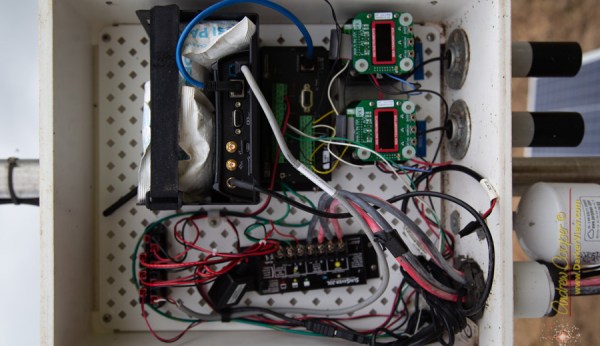

The task involves a little bit more than just mounting five Pi4s in a chassis and calling it done. There is an Ethernet switch connecting all the modules to the network, and each Pi has a comparatively bulky SSD drive + enclosure attached. By far the most annoying part of the assembly is the power supply and distribution cabling, which is further complicated by remote controlled power switching relays (one of the computers is dedicated to power management and can shut the other four modules on and off).

Even if you’re not planning on building your own server, check out the thoroughly documented assembly process and parts list — we particularly liked the USB connector to screw terminal breakout connector that he’s using for power distribution. For all the detailed information, assembly instructions and photos, we think a top-level block diagram / interconnection drawing would be very helpful for anyone trying to understand or replicate this project.

There are a lot of connections in this box, and the final result has a messy look-and-feel. But in fairness to [Paul]’s craftsmanship, there aren’t many other ways to hook everything together given the Raspberry Pi form-factor. Maybe a large and costly PCB or using CM4 modules instead of Raspberry Pi boards could help with cable management? In the end, [Paul] reckons he shelled out about $800 for this unit. He compares this expense with some commercial options in his writeup, which shows there are some cheaper and more powerful solutions. But while it may be cheaper to buy, we understand that strong urge to roll your own.

We’ve written about many Pi cluster projects in the past, including this one which contains a whopping 750 Raspberry Pis. Have you ever used a colocation service, and if so, did you use a DIY or an off-the-shelf server?