As the global vaccination effort rolls out in many countries, people will increasingly be required to provide evidence for various reasons, especially travelers. Earlier this month a coalition which includes Microsoft, the Mayo Clinic, Oracle, MITRE, and others announced an effort to establish digital vaccination records called the Vaccination Credential Initiative (VCI). This isn’t going to be a brand new thing, but rather an initiative to provide digital proof-of-vaccination to people who want it, using existing open standards:

- Verifiable Credentials, per World Wide Web Consortium Recommendation (VC Data Model 1.0)

- Industry standard format and security, per the Health Level Seven International (HL7) FHIR standard

In addition, the World Health Organization formed the Smart Vaccination Certificate Working Group in December. Various other countries and organizations also have technical solutions in the works or already deployed. If a consensus doesn’t form soon, we can see this quickly becoming a can of worms. Imagine having to obtain multiple certifications of your vaccination because of non-uniform requirements between countries, organizations, and/or purposes.

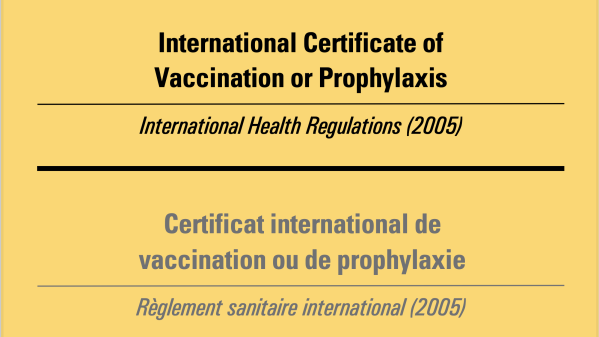

Older readers and international travelers may be wondering, “don’t we already have a vaccination card system?” Indeed we do: the Carte Jaune or Yellow Card. The concept of a “vaccination passport” was conceived and agreed upon at the International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation in 1933. Over the years the names and diseases of interest have changed, but since 2007 it has been formally called the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP). In recent times, yellow fever was the only vaccination of interest to travelers, but other vaccinations or booster shots can be recorded as well. One problem with the paper Yellow Card is that it is ridiculously easy to forge. Nefarious or lazy travelers could download it from the WHO site, print it on appropriate yellow card stock, and forge a doctor’s signature. The push for a more secure ICVP is not completely unreasonable.

Reading the instructions on the Yellow Card brings up a couple of interesting points:

- This certificate is valid only if the vaccine or prophylaxis used has been approved by the World Health Organization — Currently the Pfizer vaccine is the only one to be approved by WHO, and even that is only an emergency approval. If you receive a non-Pfizer vaccination, what then?

- The only disease specifically designated in the International Health Regulations (2005) for which proof of vaccination or prophylaxis may be required as a condition of entry to a State Party, is yellow fever — This one is interesting, and suggests that member states cannot require proof of Covid19 vaccination as an entry requirement, a situation that will no doubt be quickly revised or ignored.

Note: This writeup is about vaccinations, not about immunity. While immunity certificates have been used from time to time throughout modern history, the concept of an international immunity passport is not well established like the ICVP.