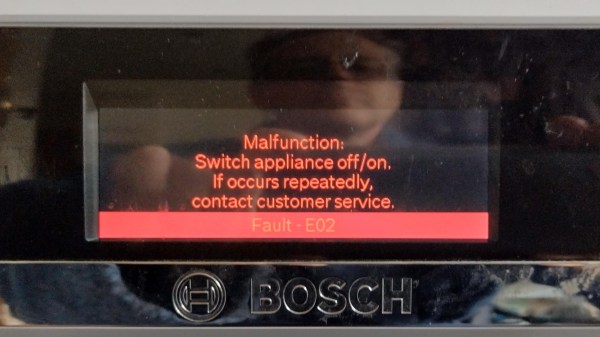

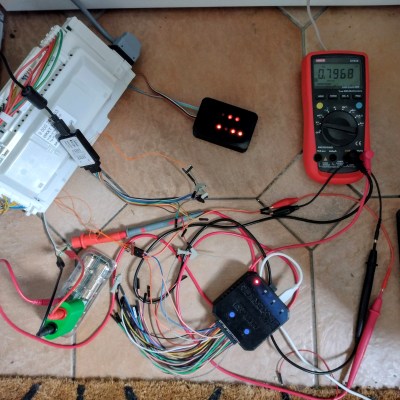

It all started with a vague error code (shown in the image above) on [nophead]’s Bosch SMS88TW01G/01 dishwasher, and it touched off a months-long repair nightmare that even involved a logic analyzer. [nophead] is normally able to handily diagnose and repair electronic appliances, but this time he had no idea what he was in for.

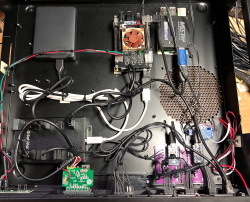

Not only were three separate and unrelated faults at play (one of them misrepresented as a communications error that caused a lot of head-scratching) but to top it all off, the machine is just not very repair-friendly. The Bosch device utilized components which are not easily accessible. In the end [nophead] prevailed, but it truly was a nightmare repair of the highest order. So what went wrong?

One error appears to have been due to a manufacturing problem. While reverse-engineering the electronics in the appliance, [nophead] noticed a surface-mounted transistor that looked crooked. It was loose to the touch and fell into pieces when he attempted to desolder it. This part was responsible for switching an optical sensor, so that was one problem solved.

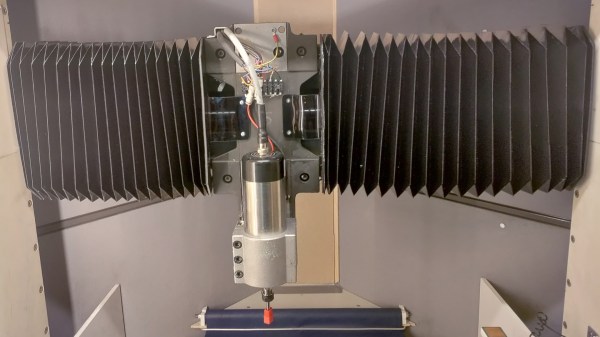

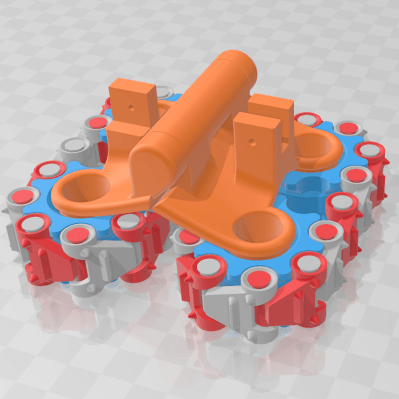

Another issue was a “communications error”. This actually came down to ground leakage due to a corroded and faulty heater, and to say that it was a pain to access is an understatement. Accessing this part requires the machine to be turned upside down, because the only way to get to it is by removing the base of the dishwasher, which itself requires a bizarre series of awkward and unintuitive steps to remove. Oh, and prior to turning the machine upside down, one has to purge the sump pump, which required a 3D-printed adapter… and the list goes on.

And the E02 error code, the thing that started it all? This was solved early in troubleshooting by changing a resistor value by a tiny amount. [nophead] is perfectly aware that this fix makes no sense, but perhaps it was in fact related to the ground leakage problem caused by the corroded heater. It may return to haunt the future, but in the meantime, the machine seems happy.

It goes to show that even though every fault has a cause and a reason, sometimes they are far from clear or accessible, and the road to repair is just a long slog. Heck, even phones these days can be bricked by accidentally swapping a 1.3 mm screw for a 1.2 mm screw.