[Ben Bartlett] recently got engaged, and the proposal had a unique bit of help in the form of a 3D-printed hexagonal mirror array, whose mirrors are angled just right to spell out a message with the reflections. A small test is shown above projecting a heart, but the real deal was a bigger version reflecting the message “MARRY ME?” into sand at sunset. Who could say no to something like that? Luckily for all of us, [Ben] shared all the details of what went into designing and building such a thoughtful and fascinating device.

Essentially, the array of mirrors works a bit like a projector. Each individual reflection can be can be thought of as a pixel, and the projected position of each can be modified by the precise angle of each mirror. With the help of some Python code, [Ben] calculated the exact angles needed to spell out “MARRY ME?” and generated the necessary 3D model. A smaller-scale test (shown in the header image above) was successful, and after that it was just a matter of printing the array and gluing on some mirrors.

Of course, that’s the short version. In practice there were quite a few troublesome issues that demonstrated the value of using early tests to discover hidden problems. For one thing, mirror angle and alignment is crucial, which meant that anything that could affect the shape of the array was a potential problem. Glue that expands or otherwise changes shape as it dries or cures could slightly change a mirror’s angle, so cyanoacrylate (CA) glue was preferred. However, the tiniest bit of CA glue will mess up a mirror’s surface in a hurry, so care was needed during assembly.

Another gotcha was when [Ben] suddenly realized, twenty hours into printing the final assembly, that the message needed to be reversed! As designed, the array he was printing would project “?EM YRRAM” and this wasn’t caught during testing because the test pattern (a heart) was symmetrical. Fortunately there was time to correct the error and start again, but it was close. [Ben]’s code has an optional visualization function, which was invaluable for verifying that things would actually turn out as expected. As it happens, the project took right up to the last minute to complete and there wasn’t quite time to check everything 100% before the big moment, but it all turned out alright. What’s life without a little mystery and danger, anyway?

The pictures are great, but you won’t regret taking the time to read through the project page (don’t miss the annotated Python code) because [Ben] goes into just the right level of detail. The end result looks fantastic, and makes an excellent keepsake with a charming story.

How was this accomplished? First of all, Winston and his team researched the correct “look” for the splash impacts by firing projectiles into mud and painstakingly working to duplicate the resulting shapes. These realistic-looking crater sculpts were then cast in some mixture of foam rubber, and given a chromed look by way of vacuum metallizing (also known as

How was this accomplished? First of all, Winston and his team researched the correct “look” for the splash impacts by firing projectiles into mud and painstakingly working to duplicate the resulting shapes. These realistic-looking crater sculpts were then cast in some mixture of foam rubber, and given a chromed look by way of vacuum metallizing (also known as

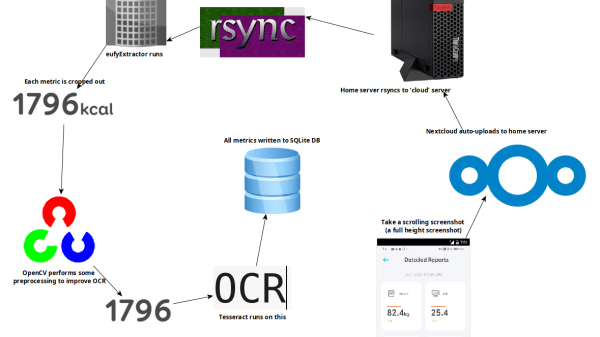

First of all, while OCR can be reliable, it needs the right conditions. One thing that ended up being a big problem was the way the app appends units (kg, %) after the numbers. Not only are they tucked in very close, but they’re about half the height of the numbers themselves. It turns out that mixing and matching character height, in addition to snugging them up against one another, is something tailor-made to give OCR reliability problems.

First of all, while OCR can be reliable, it needs the right conditions. One thing that ended up being a big problem was the way the app appends units (kg, %) after the numbers. Not only are they tucked in very close, but they’re about half the height of the numbers themselves. It turns out that mixing and matching character height, in addition to snugging them up against one another, is something tailor-made to give OCR reliability problems.