All things considered, modern photography is pretty easy. It’s really just a matter of pointing the camera at the thing you want to take a picture of and letting the camera do the rest. But that doesn’t mean good photographs are easy to make, especially when fine detail is required. And that’s the reason this 3D printed coaxial lighting setup was built — to make quality photographs of small objects a snap.

The objects of [Peter Lin]’s photographic desire are coins, no doubt of the collectible variety. Since the condition of a coin is essential to determining its value, numismatic photographers really need to be meticulous about the quality of their work. The idea here is to keep the incoming light parallel to the optical axis of the camera, for which purpose ring lights around the camera lens are often used. But they can result in lighting artifacts, and can be awkward to use for such smaller subjects.

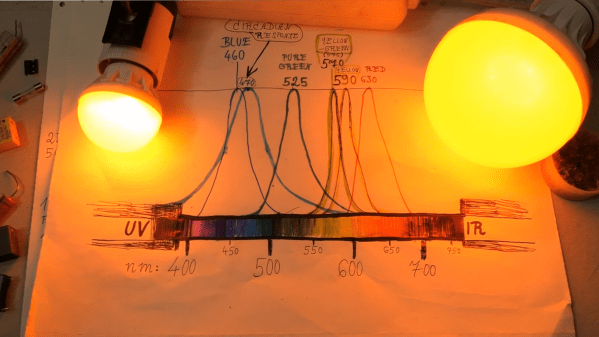

So for this setup, [Peter] essentially built a beam-splitter. The body is a printed block that’s painted matte black to keep reflections down; a little self-adhesive flocking paper helps with that too. The round aperture on the top is for the camera lens, with the square window on the side admitting light. The secret is a slot oriented at 45 degrees to both of those openings, into which the glass element from a cheap UV filter is inserted. The filter acts like a beam splitter which reflects light down onto the coin on the bottom of the block and lets it pass up into the camera lens directly above the coin, parallel to the optical axis. Genius!

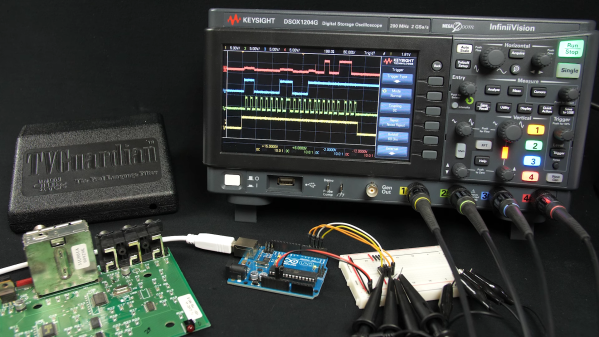

The video below shows it in use with both DSLR and smartphone cameras, and the image quality is amazing. While most of us probably aren’t photographing coins, we do enough high-resolution photography of small objects that this seems applicable. In a way, it reminds us of [Big Clive]’s “TupperCam” method of high-res PCB photography (final item).

Continue reading “Bring Out The Fine Detail In Small Objects With This Coaxial Lighting Rig”