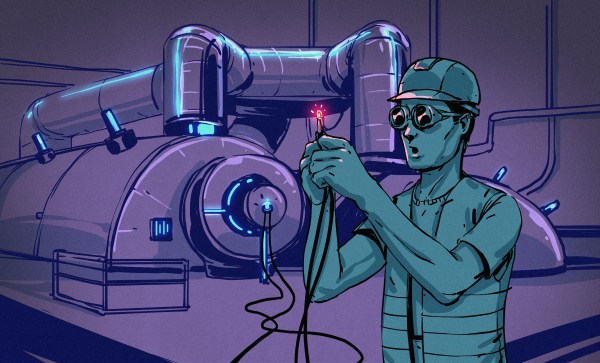

[Niklas Roy] obviously had a great time building this generative art cabinet that puts you in the role of the curator – ever-changing images show on the screen, but it’s only when you put your money in that it prints yours out, stamps it for authenticity, and cuts it off the paper roll with a mechanical box cutter.

If you like fun machines, you should absolutely go check out the video, embedded below. The LCD screen has been stripped of its backlight, allowing you to verify that the plot exactly matches the screen by staring through it. The screen flashes red for a sec, and your art is then dispensed. It’s lovely mechatronic theater. We also dig the “progress bar” that is represented by how much of your one Euro’s worth of art it has plotted so far. And it seems to track perfectly; Bill Gates could learn something from watching this. Be sure to check out the build log to see how it all came together.

You’d be forgiven if you expected some AI to be behind the scenes these days, but the algorithm is custom designed by [Niklas] himself, ironically adding to the sense of humanity behind it all. It takes the Unix epoch timestamp as the seed to generate a whole bunch of points, then it connects them together. Each piece is unique, but of course it’s also reproducible, given the timestamp. We’re not sure where this all lies in the current debates about authenticity and ownership of art, but that’s for the comment section.

If you want to see more of [Niklas]’s work, well this isn’t the first time his contraptions have graced our pages. But just last weekend at Hackaday Europe was the first time that he’s ever given us a talk, and it’s entertaining and beautiful. Go check that out next. Continue reading “Generative Art Machine Does It One Euro At A Time”