The Amazon Dash button is now in its second hardware revision, and in a talk at the 33rd Chaos Communications Congress, [Hunz] not only tears it apart and illuminates the differences with the first version, but he also manages to reverse engineer it enough to get his own code running. This opens up a whole raft of possibilities that go beyond the simple “intercept the IP traffic” style hacks that we’ve seen.

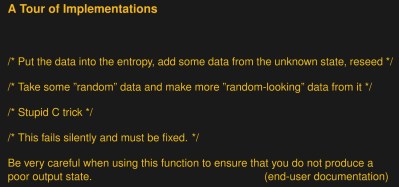

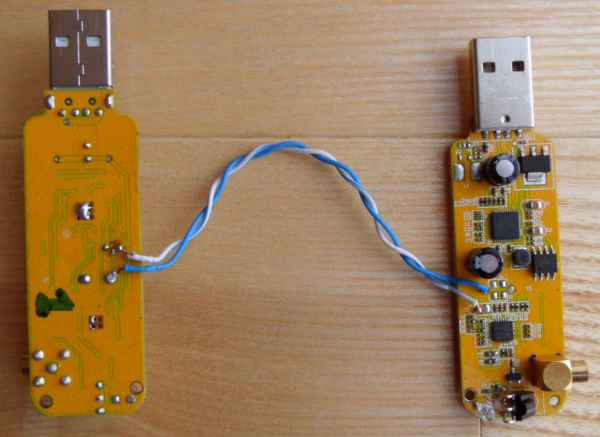

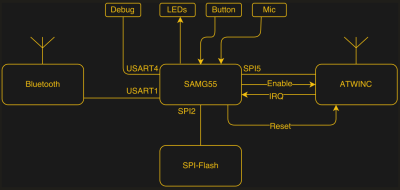

Just getting into the Dash is a bit of work, so buy two: one to cut apart and locate the parts that you have to avoid next time. Once you get in, everything is tiny! There are a lot of 0201 SMD parts. Hidden underneath a plastic blob (acetone!) is an Atmel ATSAMG55, a 120 MHz ARM Cortex-M4 with FPU, and a beefy CPU all around. There is also a 2.4 GHz radio with a built-in IP stack that handles all the WiFi, with built-in TLS support. Other parts include a boost voltage converter, a BTLE chipset, an LED, a microphone, and some SPI flash.

Just getting into the Dash is a bit of work, so buy two: one to cut apart and locate the parts that you have to avoid next time. Once you get in, everything is tiny! There are a lot of 0201 SMD parts. Hidden underneath a plastic blob (acetone!) is an Atmel ATSAMG55, a 120 MHz ARM Cortex-M4 with FPU, and a beefy CPU all around. There is also a 2.4 GHz radio with a built-in IP stack that handles all the WiFi, with built-in TLS support. Other parts include a boost voltage converter, a BTLE chipset, an LED, a microphone, and some SPI flash.

The strangest part of the device is the sleep mode. The voltage regulator is turned on by user button press and held on using a GPIO pin on the CPU. Once the microcontroller lets go of the power supply, all power is off until the button is pressed again. It’s hard to use any less power when sleeping. Even so, the microcontroller monitors the battery voltage and presumably phones home when it gets low.

Continue reading “33C3: Hunz Deconstructs The Amazon Dash Button”