Back in the days of 16-bit home computers, the one to have if your interests extended to graphics was the Commodore Amiga. It had high resolutions for the time in an impressive number of colours, and thanks to its unique video circuitry, it could produce genlocked broadcast-quality video. Here in 2023 though, it’s all a little analogue. What’s needed is digital video, and in that, [c0pperdragon] has our backs with the latest in a line of Amiga video hacks. This one takes the 12-bit parallel digital colour that would normally go to the Amiga’s DAC, and brings it out into the world through rarely-used pins on the 23-pin video connector.

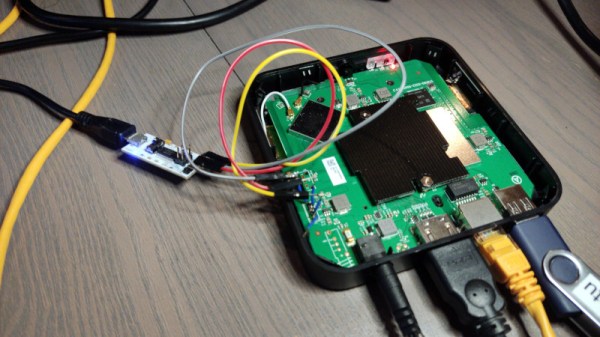

This follows on from a previous [c0pperdragon] project in which a Raspberry Pi Zero was used to transform the digital video into HDMI. This isn’t a hack for the faint-hearted though, as it involves extensive modification of your treasured Amiga board.

It is of course perfectly possible to generate HDMI from an Amiga by using an external converter box from the analogue video output, of the type which can be bought for a few dollars from online vendors. What this type of hack gives over the cheap approach is low latency, something highly prized by gamers. We’re not sure we’re ready to start hacking apart our Amigas, but we can see the appeal for some enthusiasts.